I HAD a revealing conversation with a Year 10 class last week. They asked me what I thought about the repatriation of the Elgin Marbles. ‘Should they be sent back to Greece?’ one asked. Initially surprised by an unexpected foray into current affairs, I demurred from committing to a position, concerned that the wrong answer could land me in hot water with my woke colleagues, and aware of my professional obligation to remain neutral.

My pupils’ awareness of such an important issue was encouraging, but a closer examination exposed a troubling ignorance. Every student willing to express an opinion, many with a worrying degree of certitude, said that the marbles should be returned because the ‘British stole them’. You must also return the Benin Bronzes for the same reason, they collectively opined.

Their use of the words ‘British’ and ‘you’ to address the country responsible for these so-called injustices was striking. I was standing in front of a group of mainly Asian-Brits (I work in a diverse school with a large percentage of Muslim students) who do not feel British. The week before, pupils in the same class decried the fact that we don’t have enough Muslim history on the curriculum. ‘It’s all about blacks and whites,’ they said.

But where are they picking up this one-sided take on the Elgin Marbles and Benin Bronzes, facilitating their estrangement from their home country? Well, notwithstanding the suspicion that ignorant and ideologically driven parents are influencing their kids, anti-British disinformation is everywhere. It is therefore no surprise that they are absorbing a simple, dualistic, good-versus-evil, interpretation of history disseminated by many of our self-loathing cultural institutions.

Just look at the BBC’s recent coverage of the spat between Rishi Sunak and the Greek prime minister. They’ve taken to referring to the marbles as the Parthenon Marbles rather than the Elgin Marbles – a transparent, politically motivated nod to the Guardian line (remember, the most-read newspaper in BBC studios) that they belong in Greece.

When it comes to the Benin Bronzes, moreover, the Charity Commission has also drunk the Guardian kool-aid, concurring with the paper’s misleading claim that ‘they [the bronzes] were looted in 1897, when British forces sacked the Benin kingdom, in modern-day Nigeria, burning down the royal palace, exiling the Oba, and seizing all royal treasures’. Indeed, in a statement, the commission said that the University of Cambridge is ‘under a moral obligation’ to return the artefacts. It’s amazing that such a little-read newspaper has such prodigious cultural reach.

However, despite the self-loathing milieu that presents Britain as uniquely evil and refuses to consider the context in which the acquisition of these treasures took place – providing much-needed nuance and objectivity – their previous teacher is perhaps most to blame for feeding them misinformation. And she’s no exception, believe me.

She forced the pupils to write to the University of Cambridge, urging the rector to hand the Benin Bronzes back to the Nigerian government.

In such circumstances, I decided to provide some much-needed balance. Handing back the Bronzes is not quite as straightforward as it first appears. First, their acquisition was not a simple case of colonial theft. According to the historian Andrew Roberts, the expedition involved was in response to the massacre of a peaceful British delegation. The Oba (king) of Benin was a violent, slave-holding monarch who often raided his neighbours to enslave their inhabitants. Furthermore, when the British arrived in Benin, they ‘found hundreds of dead and dying slaves, some beheaded, crucified or disembowelled’. The expedition saved lives and liberated many of the slaves. It also led to the Oba’s exile and the acquisition of the Bronzes, many soaked in the blood of the sacrificed slaves.

Sending the Bronzes back is understandably opposed by the descendants of those enslaved by the Oba – their ancestors, after all, paid in blood for the purchase of the bronze used to make the sculptures. They do not want the descendants of slave-holders – particularly the current Oba (who’s been promised restitution by the Nigerian government) – to benefit from the suffering of their ancestors. They want them to be kept in Cambridge and elsewhere.

They had clearly not heard this part of the story before writing their letters.

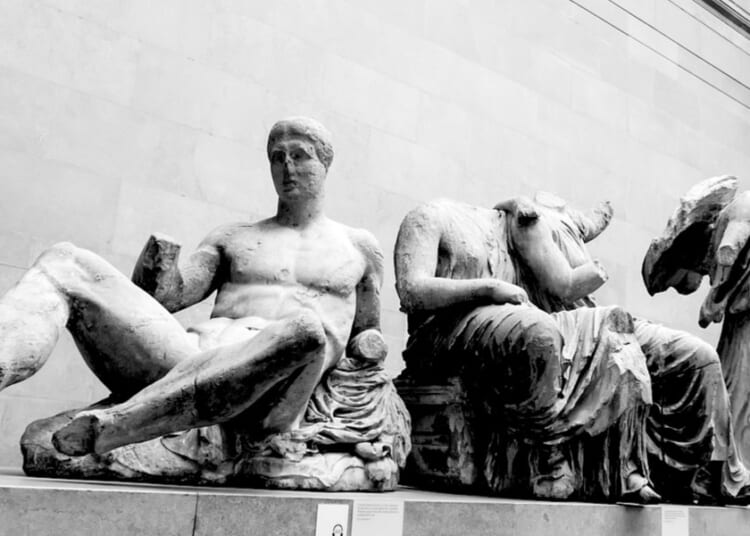

The acquisition of the Elgin Marbles also deserves some context. They were not ‘stolen’ by the Earl of Elgin, as claimed. The British Ambassador to Constantinople legally purchased them from the Ottoman authorities in Greece. Furthermore, Elgin saved the marbles from probable destruction. The Parthenon was being used as an ammunition dump, had been badly damaged by explosions and was in the process of being ‘cannibalised by Turkish dragomen selling off bits as souvenirs to tourists’. Without Elgin they could and probably would have been lost for ever.

Why was my predecessor so reluctant to explore these fascinating complexities? Did she not have time to research them? Is she so ideologically wedded to postcolonialism that she deliberately ignored them? Or has she been so completely brainwashed by the predominance of anti-British propaganda that she had lost the ability to seek and recognise nuance?

Whatever the reason, and, for what it’s worth, I suspect the latter, it’s had a deleterious impact on my pupils. They are full of resentment and anti-British sentiment. More worrying, however, is the fact that my school is no exception. Brainwashed teachers are brainwashing our children.