Friedrich Nietzsche, in Beyond Good and Evil, targets Christianity, in the form most accessible to him: Catholicism. He critiques the virtues it fosters and the religion’s effects, particularly highlighting Christianity’s stance on suffering. On the other hand, Martin Luther King Jr. rejects Nietzsche’s accusations of Christian notions encouraging mediocrity and weakness. Despite both philosophers’ adherence to drastically opposing schools of thought—one embracing a moral standard and the other rejecting it altogether (especially Christianity)—they both find suffering to be beneficial and valuable. King sees the capacity to endure suffering as a measure of love, specifically a love that serves as a weapon against evil. Nietzsche finds value in suffering as a sign of resistance on the path to achieving goals. Both welcome suffering as an inescapable, unavoidable meeting of obstacles. For Nietzsche, suffering is a part of the “will to power” and for King, it is a part of “loving thy neighbor.” Nietzsche’s “will to power” falls short, concerning individual goals exclusively. King’s “love thy neighbor” concerns goals that have both physical and spiritual implications that transcend the immediate direct goals of the individual. The role of suffering for Nietzsche and King, though different in practice, works towards both of their goals. The “free-spirit’s” goals are directed inward, while the Christian’s is directed upward towards a purpose that transcends the self. Despite Nietzsche’s insistence in Beyond Good and Evil that the Christian notion of “loving thy neighbor” is antithetical to humankind’s survival, King in his Strength to Love argues it is necessary for spiritual survival and tangible accomplishment.

Friedrich Nietzsche, in Beyond Good and Evil, targets Christianity, in the form most accessible to him: Catholicism. He critiques the virtues it fosters and the religion’s effects, particularly highlighting Christianity’s stance on suffering. On the other hand, Martin Luther King Jr. rejects Nietzsche’s accusations of Christian notions encouraging mediocrity and weakness. Despite both philosophers’ adherence to drastically opposing schools of thought—one embracing a moral standard and the other rejecting it altogether (especially Christianity)—they both find suffering to be beneficial and valuable. King sees the capacity to endure suffering as a measure of love, specifically a love that serves as a weapon against evil. Nietzsche finds value in suffering as a sign of resistance on the path to achieving goals. Both welcome suffering as an inescapable, unavoidable meeting of obstacles. For Nietzsche, suffering is a part of the “will to power” and for King, it is a part of “loving thy neighbor.” Nietzsche’s “will to power” falls short, concerning individual goals exclusively. King’s “love thy neighbor” concerns goals that have both physical and spiritual implications that transcend the immediate direct goals of the individual. The role of suffering for Nietzsche and King, though different in practice, works towards both of their goals. The “free-spirit’s” goals are directed inward, while the Christian’s is directed upward towards a purpose that transcends the self. Despite Nietzsche’s insistence in Beyond Good and Evil that the Christian notion of “loving thy neighbor” is antithetical to humankind’s survival, King in his Strength to Love argues it is necessary for spiritual survival and tangible accomplishment.

Nietzsche introduces his thoughts on pain and suffering by explaining how morality is formed. He states, “moralities are merely a sign language of the affects,” or emotions. The way we approach theodicy or “the problem of evil” defines our morality or set of ethical standards. Our explanations regarding suffering grant insight into the image of ourselves that we demand existence to reflect. Before commenting on the solution to “the problem of evil,” one must define the nature of pain, or suffering. Nietzsche understands pain to be “the work of the intelligence” that “serves the function of evaluation marking out certain states and conditions as undesirable.” Pain has no other purpose than to serve as an emotional thermometer that responds to likes and dislikes. Suffering may not necessarily be evil innately, but the only thing worse than suffering itself is suffering with no meaning or direction. Nietzsche comments, “human beings… cannot live with meaningless suffering—suffering for no reason at all,” according to scholar Philip Kain. However, an elevated, indirect, ultimate purpose of pain and suffering may be intentionally unknowable. Nietzsche thinks “it might be a basic characteristic of existence that those who would know it [suffering] completely would perish.” Thus, spiritual strength is indicative of the amount of truth one can know and understand at its most primal, genuine, blunt level. Furthermore, suffering is the “only” virtue that “has created all enhancements of man so far” and it is naïve to think that suffering could be “abolished”; it can only be concealed. Regardless of the extent to which we think we can dull pain, suffering “is fundamental and central to life. The very nature of things, the very essence of existence, means suffering.” Suffering is an inevitable actuality of life that can be used to serve human means through spiritual strength, as opposed to the Christian notion of pain that implies suffering must be alleviated with the hereafter’s spiritual ideal of a painless existence in mind.

The Christian response to suffering leads Nietzsche to describe Christianity as “the religion of pity” and claims therein exists a “ladder of religious cruelty.” First, self-denial, a characteristic of Christianity, asks the individual to suppress instinct, or “nature,” to promote suffering. After consistently chipping away at nature through restraint (e.g. fasting), it is thought that there is nothing else to sacrifice. However, on the last rung of the ladder, people “sacrifice God himself and, from cruelty against oneself.” The ladder of cruelty creates the romanticization of suffering, “mak[ing] their [human beings’] own sight tolerable to them… refreshing, refining, makes the most of suffering, and in the end even sanctifies and justifies. Christians’ attitude toward suffering symbolizes the meaning they ascribe to it, and the contentment they assign to their life. According to Nietzsche, contentment prevents free-spirits from rising from the herd and keeps them as slaves in the slave-master relationship civilization cultivates; Christianity promotes virtues such as complacency, obedience, and subservience. As long as people take up the position of slave in the slave-master relationship, they will never live up to their ultimate potential. As a result, Nietzsche warns against attachment to pity for others, another side-effect of the Christian disease. He warns against pity, “not even for higher men into whose rare torture and helplessness some accident allowed us to look.” Pity “attempt[s] to impose our [one’s] own meaning” on suffering, cheapening it. Nietzsche would rather empower those suffering than belittle them and subjugate the well-intentioned to the suffering itself. By empowering the sufferer, he promotes the individuality that lays the foundation of his “will to power” doctrine.

Another characteristic of Christianity, Nietzsche notes, is the notion of preservation, which aids in the appreciation of suffering. By viewing life as sacred, Christians attempt to protect life in all its forms and in whatever capacity. Nietzsche thus denotes Christianity as a religion “for sufferers, they [Christians] agree with all those who suffer life like a sickness.” They seek to preserve “the type that has so far suffered the most,” who is held in the most esteem. The virtue of suffering aims to preserve life and master one’s nature via self-denial. Ultimately, the virtues Christianity perpetuates are associated with the herd morality that prohibits people from becoming the free-spirits, or the masters Nietzsche encourages his readers to become as a means of rising to fulfill their potential.

At the heart of the Christian response to suffering are the eventual eradication of it and the qualities that are cultivated as a result of pain. Christianity encourages notions like “equality of rights” and “sympathy for all that suffers”—and suffering itself may take for something that must be abolished.” The constant battle against suffering comes from a belief that there is a world without it. Christians pursue something that is impossibly unattainable, which is the total eradication, or “complete absence of suffering.” Nietzsche denies the existence of a world without suffering, alternate or otherwise. So, a solution exists where the inevitability of suffering must serve a purpose. And that solution does not necessarily have to reside outside or above oneself. Scholar Maudemaire Clark posits: he asks, “why would it not be enough to recognize why that suffering is necessary for the realization of many of life’s goods”? The solution resides within.

Nietzsche invites readers to look within themselves to find value in suffering, specifically in terms of how they can utilize it to attain their goals. According to scholar Bernard Reginster, “Nietzsche thought a revaluation of ‘the dominant, life-negating values must show that… to affirm life, we must therefore show that suffering is good for its own sake.” Suffering is beneficial in itself insofar as it exists in the process of overcoming resistance or satisfying desire. The purpose of suffering makes his conception of the “will to power” all the clearer when he defines the “will to power” as “exercising volition, command[ing] at the same time and identify[ing] with the execut[ion].” Not only does the person exercising their will to power enjoy the satisfaction of overcoming the obstacle but there is an added, extra sense of pleasure at the fact that their intent or drive was the catalyst for the success. This phenomenon occurs when the “will” and carrying out of the “action” are connected if not a singular process altogether. The extra pleasure is the feeling of superiority and power that accompanies the “discharge of strength” that takes place during the process of encountering resistance.

Suffering is a necessary component in the process of achieving success and accomplishing goals. In fact, Clark argues suffering is critical, or “essential” to these pursuits. Thus, Clark deduces, “if power consists in overcoming resistance, then we must will suffering, because suffering is simply the experience of resistance to our will.” To manifest the will of the individual, suffering must be a cultivated discipline, whether that implies experiencing it or inflicting it on others. A world without suffering would be a world without struggle or oppression, which is necessary to Nietzsche’s slave-master morality conception where the free-spirit must be the master in this slave-master dynamic. A world without “challenges to be met” would be a world not worth living in for Nietzsche. Rather than aim for a final state like Christianity does, Nietzsche argues “we should affirm life itself, the process, the activity of living that does not find its value in some end state at which it aims” (Clark 97). The value of suffering is intrinsic to the process itself. Affirming life looks like “love[ing] every single moment in our lives, every single moment of suffering.” The “will to power” is not only life-affirming, but it also makes suffering a discipline, which requires a mastery of temptation and of one’s own inclinations. If people are tempted by an escapist delusion of life that is more appealing because the delusion leaves out the unpleasant aspects of reality, psychological control is lost. People become slaves, “slipping back into a state of subjugation,” instead of masters because they will have lost control over their “psychological stranglehold” (Kain 57). Unlike the Christian notion, suffering as a sign of impending resistance “strip[s]” connotations of “sin, punishment, or guilt.” This not only promotes individual agency, it protects the sufferer against psychological “subjugation.” Suffering as a sign of resistance, the next step to achieving one’s goals, is more positive than suffering serving as a means of punishment.

Martin Luther King Jr. holds a different perspective on suffering. As a solution to combat suffering in the context of racial oppression, he echoes Jesus’ “admonition” to “love thy neighbor” in his Strength to Love. Leading with Matthew 5:43-45, he begins by responding to Nietzsche’s criticism of Christian love. Then, he begins to outline the steps to “love thy neighbor”. One’s capacity to love directly correlates with one’s capacity to forgive. Forgiveness is defined as “reconciliation,” when “the evil act no longer remains a barrier to the relationship.” After understanding forgiveness, one must understand that an evil act does not define the person. Recognizing there is an element of good in everyone facilitates our ability to love others and hate them less. King writes, “When we look beneath the surface, we see within our enemy-neighbor a measure of goodness and know that the… evilness of his acts are not quite representative of all that he is”. Once one recognizes the nuance and complexity of humanity, does one understand that no one is completely good or completely evil. This notion forces us to investigate why people think the way they do or act the way they do. We ask ourselves why people commit the evil they do and how evil intentions arise. We learn “hate grows out of fear, pride, ignorance, prejudice, and misunderstanding”. Meanwhile, the notion of people serving as God’s image or a reflection of Him in some manner (Genesis 1:6) permeates our desire to forgive and love others. This is how forgiveness ultimately begins, by remembering all humanity as a reflection of God. Once forgiveness and the reality of man’s reflection of God is understood, our intentions must be reassessed. “We must not seek to defeat or humiliate the enemy, but to win his friendship and understanding.” The love we are to extend to our enemies is agape in the Greek. “Agape... the love of God operating in the human heart” is the “level” in which we are to “love thy neighbor”. The only reason we ought to love others is simply “because God loves [them]”. King encourages to hate the evil act committed but warns against hating the person committing the act itself. Otherwise, it would mean defying God and failing to accurately represent Him. Loving our fellow human is a symbol of the image of God we are called to reflect, according to King. And oftentimes, that looks like forgiveness, friendship, and understanding. The command to “love thy neighbor” implies an act that transcends the “aesthetic appeal” (eros) to another, an “understanding and creative, redemptive goodwill for all men.”

King argues there are direct and indirect effects that result from loving one’s neighbors. A direct effect is the disruption of the cycle of violence revenge, or “returning hate for hate” perpetuates. Hate does nothing to alleviate or de-escalate the hostile situation. It sets forth a domino effect that sees no end. Hate cannot defeat hate, rather it latches on to it and increases in multitude. Only love can drive out hate. Hate breeding hate develops harmful effects on one’s soul, “scar[ring] the soul and distorting the personality”. Hate not only harms the victim but also harms the oppressor just as much. “Like a… cancer, hate destroys a man’s sense of values and his objectivity.” Love is the only cure, uniting the personality in the very same way hate divided it. Because of love’s transformative effect, it “is the only force capable of transforming an enemy into a friend”. Love has a rehabilitative, “redemptive,” and “reconciliatory” nature that ultimately proves transformative. Love “creates and builds up” rather than destroys, preserving personality, objectivity, values, etc. These very qualities are what make up the soul; love essentially preserves the soul.

Love’s indirect effects lay outside the person; it transcends. Unlike Nietzsche’s assertion that “loving thy neighbor” has direct, physical effects, King posits love has spiritual implications in addition. Love enrichens the relationship between God and humankind. Not only does love perpetuate an accurate reflection of God but love also is the only way in which one can “know God and experience the beauty of his holiness.”

Practical ways in which victims can love their enemies is through suffering. Addressing relations between the black community and white segregationists, King declares to the oppressors, “we shall match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering”. The capacity to love is measured by the capacity to “endure suffering” and forgive. While Nietzsche would argue that suffering serves no more than a means to an end, King sees it as something more. Pain and suffering are a weapon, manifested in love, that defeats hate and brings mankind closer to God. He warns, “But be ye assured that we will wear you down by our capacity to suffer. One day we shall win freedom, but not only for ourselves… we shall win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.” King envisions suffering as an active resistance, rather than Nietzsche’s view of Christian suffering as passive endurance that simply weakens rather than strengthens. Suffering’s function, according to Nietzsche, is consistent with King’s perspective. King explicitly describes a victory that results from the capacity to endure suffering. The goal is to defeat racism stemming from hatred that holds roots in “ignorance, pride, prejudice,” etc. Enduring suffering out of love for the oppressor will not only accomplish this, but it will also accomplish the strengthening of the relationship between the oppressed and God (a spiritual telos).

Both Nietzsche and King agree that suffering is useful for its own sake. To Nietzsche, suffering is life-affirming and serves the “will to power” in the process of overcoming obstacles to accomplish goals. However, his view is limited by physical implications. Nietzsche does not see any value outside of the sufferer; the value is completely contingent on the individual meaning derived from it. There is inherent value to suffering simply because it is a part of the vast smorgasbord of emotions that constitutes living, simply because it is a part of the act of living or life itself. Suffering’s function, according to Nietzsche, is to affirm life and serve as a means of resistance in the pursuit of goals. King on the other hand, finds value in suffering that not only has direct, physical implications, but spiritual implications too. He views suffering not as a weapon that just signifies mere resistance, but as a weapon forged out of love that serves as the resistance itself, the will to power to defeat evil. Both Nietzsche and King see suffering as inevitable resistance towards goals and as tools. Nietzsche sees enduring suffering as a discipline and a practice of affirming the act of living. King, on the other hand, sees suffering as an exercise in love and active resistance against evil and hatred.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Works Cited:

Kain, Philip J. “Nietzsche, Eternal Recurrence, and the Horror of Existence.” Journal of Nietzsche Studies, no. 33, 2007, pp. 49–63. JSTOR. Accessed 30 Oct. 2023.

King, Martin Luther, and Coretta Scott King. Strength to Love. Fortress, 2010.

Maudemarie Clark. “Suffering and the Affirmation of Life.” Journal of Nietzsche Studies, vol. 43, no. 1, 2012, pp. 87–98. JSTOR.

Nietzsche, Friedrich Wilhelm, and Walter Arnold Kaufmann. Basic Writings of Nietzsche. Modern Library, 2000.

O’Sullivan, Liam. “Nietzsche and Pain.” Journal of Nietzsche Studies, no. 11, 1996, pp. 13–22. JSTOR. Accessed 28 Oct. 2023.

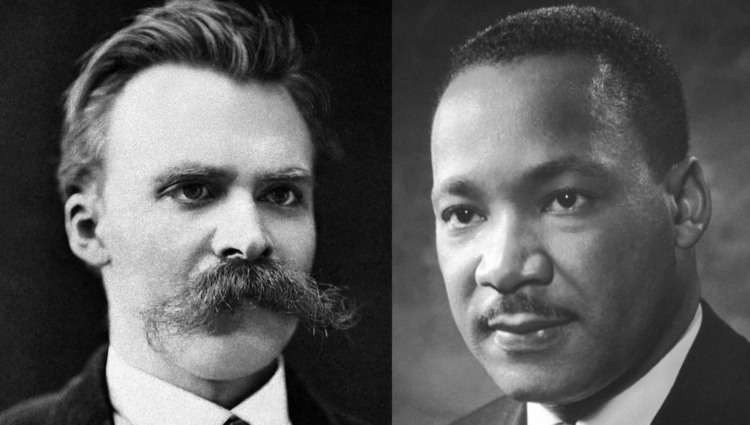

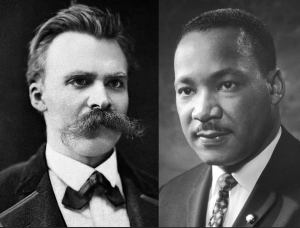

The featured image combines an image of Friedrich Nietzsche and an image of Martin Luther King Jr. Both images are in the pubic domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.