God is the complete satisfaction of our need to know and to love. He is all Truth, utterly lovable. But God must be known for what He is, else an appropriate response to Him cannot be made. Philosophy and theology tell us, but not so effectively as does Dante, who has made us see what the possession of God in heaven means.

Our Father’s House by Sr. Mariella Gable, OSB (356 pages, Cluny Media)

Here are twenty-eight short stories which ought, for one reason or another, to be of special interest to Catholics. Some of them have long since been recognized as classics. Some are distinguished short stories by the foremost practitioners of the art at the present time. Some few, by writers less well known, deserve by their merit to stand with their peers. They are collected here for the convenience of those who would like an easy access to some of the best short stories that have dealt directly with eternal verities or with the local color of Catholic life. May no one call them Catholic short stories.

Here are twenty-eight short stories which ought, for one reason or another, to be of special interest to Catholics. Some of them have long since been recognized as classics. Some are distinguished short stories by the foremost practitioners of the art at the present time. Some few, by writers less well known, deserve by their merit to stand with their peers. They are collected here for the convenience of those who would like an easy access to some of the best short stories that have dealt directly with eternal verities or with the local color of Catholic life. May no one call them Catholic short stories.

There is, however, such a thing as Catholic fiction—both of the long and short variety. And though the definition of it has long been a vexing matter, the problem at this point deserves careful consideration.

Taking a broad view of the whole field of writing, Sister Madeleva has defined Catholic literature as any literature that is treated as a Catholic would treat it. Theoretically, I believe that that definition is beyond dispute, particularly since Sister Madeleva defines the Catholic as one who is perfectly disciplined, a saint. It is only when one applies this definition as a test to specific pieces of literature that confusion arises. Measure obvious cases like Tess of the D’Urbervilles or Paradise Lost by this yardstick, and the answer is easy—they are not Catholic. But ask the question, How would a Catholic have written Kubla Khan, Rip Van Winkle, or Alice in Wonderland?—and you are immediately confronted with a problem. You would have to admit, I believe, that the Catholic artist would have written them just as they are. By this standard, then, much of the world’s great literature, though it is in no way concerned with supernatural values or with ethics, much less with the local color of Catholic life, would have to be called Catholic literature. Make a collection of such pieces, label it Catholic literature, hand it to the average Catholic, and he will frown in disappointment. This is not what he expected. I believe that the instinctive expectation of the average Catholic is correct.

In no field of writing, however, is the problem of determining what is and what is not Catholic literature so difficult as it is in fiction. It is, perhaps, an act of supererogation to add to the dispute, but I do not believe that a definition of Catholic fiction can be discovered until one has clearly understood the Catholic philosophy of personality. In fact, the correct concept of personality is a smooth spool onto which can be deftly wound all the tangled threads of the problems concerning Catholic fiction. Without it I believe that confusion must persist.

No subject has so fascinated the average person as the modern notion of personality. Everyone wants to believe that he can win friends and influence people—that charm and magnetism are to be had for the asking—if one reads the right books and pamphlets. But personality in this popular sense is not our concern here.

St. Teresa was born with a great deal of natural charm and magnetism. She had “personality.” But when she reached middle age, Our Lord showed her the place in hell which she would occupy for all eternity if she did not change her ways. She became a great saint. She developed her personality in the sense we mean here. Which is not to say that charm and magnetism are matters for eternal damnation, but it is to say that to become a great personality is a very different thing from being a charming individual.

What is a person? A person is the highest thing in nature, according to St. Thomas, and that which distinguishes him from all other beings is his intellect, his reason. Because man can know things, he responds to them according to their goodness, and loves the good he discovers. Knowing and loving, because goodness can be loved only when it is known—these are the special activities of a person, as such. We are all persons. We are not all personalities. One develops personality when one habitually makes an appropriate response to value. Thus has personality been defined by Dietrich von Hildebrand in his excellent study Liturgy and Personality.

What does it mean to make an appropriate response to value? It means that all the things we can know are ranged in a hierarchy of being, some deserving less love, some more. It means that we strive to give each thing the love it deserves, and that we are done once and for all with the feverish desire merely to be different. It does away with the romantic emphasis upon the ego. It does not ask: How do I feel about clam chowder and Gothic architecture? Do I worship baby pandas and regard moral restraint as silly? It molds the classic personality, essentially noble, admirable, and balanced. A classic personality is never absolutely achieved, but the person striving to attain its perfection habitually endeavors to make an appropriate response to value. Appropriate—that which in the hierarchy of being this particular thing deserves.

What does it mean to make an appropriate response to value? It means that all the things we can know are ranged in a hierarchy of being, some deserving less love, some more. It means that we strive to give each thing the love it deserves, and that we are done once and for all with the feverish desire merely to be different. It does away with the romantic emphasis upon the ego. It does not ask: How do I feel about clam chowder and Gothic architecture? Do I worship baby pandas and regard moral restraint as silly? It molds the classic personality, essentially noble, admirable, and balanced. A classic personality is never absolutely achieved, but the person striving to attain its perfection habitually endeavors to make an appropriate response to value. Appropriate—that which in the hierarchy of being this particular thing deserves.

Obviously it would be absurd to attempt to explore the whole range of being in order to see what appropriate responses are. But something can be done by way of illustrating the point. What are appropriate responses to nature, to man, to God? The classic personality rejoices in the beauties of nature. Its spirit is the spirit of the Benedicite—praising God, whose excellence is felt in the clouds, the hills, the streams, the winds. But nature is not honored more than it deserves. The classic personality would certainly not maintain with Wordsworth that

One impulse from a vernal wood

Can teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good

Than all the sages can.

Nor would the classic personality seek ultimate repose in nature with Thompson’s sinner flying from the Hound. Nature betrays only those who ask more of her than she can give. “Nature, poor stepdame, cannot slake my drought.” But only a warped personality would seek to drink the happiness all men desire at her pools.

The classic personality regards human love and friendship as the highest gifts in the world. Each of us is unique in God’s sight. A friend discovers our uniqueness, and there is something God-like in the honor and love he bestows upon the beloved. Man is much more tempted to rest in friends or in those loved than in nature. But if he gives more than an appropriate response to this value, the value itself betrays him. His soul will cry out with something of the anguished discovery of Shelley that there is always

The desire of the moth for the star,

Of the night for the morrow,

A devotion to something afar

From the sphere of our sorrow.

That “something afar” is God. God is the complete satisfaction of our need to know and to love. He is all Truth, utterly lovable. If we stop at less than God, our mistake can be summarized in Étienne Gilson’s memorable words:

No Christian philosopher can ever forget that all human love is a love of God unaware of itself… The question is not how to acquire the love of God, but rather how to make it fully aware of itself, of its object, and of the way it should bear itself toward this object. In this sense we might say that the only difficulty is education, or if you prefer it, re-education of love.

It is this re-education of love that is the main life work of the person struggling to become a great personality. If a person cultivates the habit of making an appropriate response to all values along the way, he will aid and not hinder the total response to be made to God’s transcendent value.

But God must be known for what He is, else an appropriate response to Him cannot be made. Philosophy and theology tell us, but not so effectively as does Dante, who has made us see what the possession of God in heaven means. In Him we shall know all that the universe has ever contained, and knowing it we shall love it. What a metaphor he invents to make us understand! Gazing at the point of light which is God he says:

Within its depths I saw ingathered, bound by love in one volume, the scattered leaves of all the universe.

The scattered leaves of all the universe—at last all together in a single volume, love the binding—there we have it. Dante’s whole Paradiso is conceived in terms of personality—knowing and loving. His definition for heaven is this: “Light intellectual full-charged with love, love of true good full-charged with gladness, gladness that transcendeth every sweetness.”

The opportunity lies open to every person to taste that reality experimentally here and now through contemplation—if he is willing to make the effort. If he is not willing to do that, he can take on faith the assertion of those who know experimentally. He must, if he is a Catholic, accept the teaching of the Church that it is so. But to those who live the life of grace, all arguments and proofs cease to be important, for such persons know simply and directly. They have discovered, with Alfred Barrett, S.J., that

The life of grace and glory is the same,

The life of grace is, by another name,

Heaven on earth, and death is but a change

In range—

And nothing strange!

Nothing strange indeed for the classic personality. He has not given an inappropriate response to the values here and now. He has recognized them for shadows of the Truth and Goodness beyond. He has made, with the mystic Jessica Powers, a discovery and a resolution:

No man can stay

In any golden moment; and no more

Will I let any trick of light betray

Me to a house that is nothing but a door.

In fact the classic personality is simply one that never mistakes a door for a house. And the house is our Father’s.

In fact the classic personality is simply one that never mistakes a door for a house. And the house is our Father’s.

This essay serves as the introduction to Our Father’s House.

Republished with gracious permission from Cluny Media.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

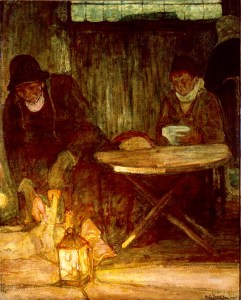

The featured image is “Etaples Fisher Folk” (1923) by Henry Ossawa Tanner, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.