In February of 2022, I began a new tradition that I hope to maintain. It stemmed from a keen desire to become more familiar with the great literary works of the 20th century. So, last year I decided to read one work published or written exactly one century in the past. Thus, 2022 corresponded to 1922. While there was a litany of books or essays to choose from, as an avid student of American conservativism I knew what work I had to read, T.S. Elliot’s The Wasteland. Yet, as someone not naturally inclined to poetry and as February turned into March I found myself binge-watching Netflix with my wife, working on editing the footnotes to my Ph.D. dissertation, or getting lost down the internet rabbit hole.

In February of 2022, I began a new tradition that I hope to maintain. It stemmed from a keen desire to become more familiar with the great literary works of the 20th century. So, last year I decided to read one work published or written exactly one century in the past. Thus, 2022 corresponded to 1922. While there was a litany of books or essays to choose from, as an avid student of American conservativism I knew what work I had to read, T.S. Elliot’s The Wasteland. Yet, as someone not naturally inclined to poetry and as February turned into March I found myself binge-watching Netflix with my wife, working on editing the footnotes to my Ph.D. dissertation, or getting lost down the internet rabbit hole.

Despite initial procrastination, I eventually immersed myself in Eliot’s masterpiece, savoring it over the course of the year. The experience left me grateful for the journey. As insightful and enjoyable as The Wasteland was I found myself looking forward to a different type of work in 2023. And, as January of the following year arrived, I faced the dilemma of selecting a new book.

I narrowed it down to three books. Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Links, Max Weber’s Wirtschaftsgeschichte, and Gresham J. Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism. Having never read any of Christie’s novels, but being fond of the genre I felt reading of one the world’s best mystery novelists would not be a negative. At the same time, I was drawn to Max Weber’s Wirtschaftsgeschichte. While not as famous as The Protestant Work Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (which I read years ago), this work would have allowed me deeper insights into Weber’s economic theories based on years of lectures. But when all was said and done, I settled on Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism being that it was recommended to me years ago by an undergraduate professor.

Gresham J. Machen was a New Testament scholar at Princeton Theological Seminary for nearly two decades beginning in 1906. A staunch opponent of modernism and a prescient critique of the detrimental effects of liberalism on orthodox Christianity, he would end up parting ways with Princeton and founding Westminster Theological Seminary and eventually the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. Machen saw liberalism not merely as a political or cultural philosophy but as a religion incompatible with traditional Christianity. He defended orthodox Christianity against the encroachment of liberal theology, presenting a clear dichotomy between the two in his writings. His first major work while in the world of academia was The Origin of Paul’s Religion (1921). It was a refutation of contemporary modernist theology which argued that the Apostle Paul’s religion was closer aligned with Greek philosophy and a break away from supernaturalist origins. Yet, this was only his initial foray into the theological doctrinal wars occurring during his tenure.

Two years later Machen released his most influential and lasting work as well as my 1923 choice, Christianity and Liberalism. After reading it, I could understand why my professor recommended it. This vatic book may be the most cogent and one of the earliest articulations against the ill effects of liberalism on orthodox Christianity. Nearly a century ahead of his time, Machen saw liberalism or modernism not as a political or cultural philosophy with its effects limited to the world of academia or the fringes of the cultural sphere but keenly observed that liberalism is a religion unto itself, where its adherents could cling to the doctrine of Christianity or the doctrine of liberalism, but not both. Machen defends traditional Christianity against the encroachment of liberalism in theology and the church and presents a clear-cut contrast on a range of issues including doctrine, God and Man, the Bible, Christ, Salvation, and the Church.

While deconstructing each chapter would be advantageous, the space provided would not do the arguments and refutations justice. Nevertheless, bringing to the spotlight two of his six points (not including his Introduction) may provide just the insight necessary to acknowledge Machen’s broader thesis and recognize the perceptive eye for seeing what was coming down the pike. First, let us engage with the view of Jesus Christ. Machen diagnosed the issue with ease and very succinctly.

According to Machen, for the liberal preacher or Christian, “Jesus…is an example for faith, not the object of faith. The modern liberal tries to have faith in God like the faith which he supposed Jesus had in God; but he does not have faith in Jesus.” Thus, some in 1920s America returned, albeit in an augmented contemporary fashion, to the failed 4th-century arguments of Arius of Alexandria. On this point, Machen beats back the ideological heresy with a trifecta of Scripture, historical knowledge, and logic, and in the process precedes C.S. Lewis’s “liar, lunatic, or Lord” phraseology, asserting “if Jesus be merely an example, He is not a worthy example; for He claimed to be far more,” thereby eluding to the fact that if Jesus is not who He claims to be then He is likely a charlatan or insane. Much more can be said on the differing views of Jesus, and Machen does indeed give evidence after evidence for nearly 40 pages on the topic, but a second point should hopefully suffice to drive the point home on not only his thesis but also on his foresight into the 21st century.

In his chapter on “Salvation,” Machen touches on several distinctions. Foremost, he deals with “exclusivity” (a term that many found egregious both then and now that goes against the grain of most modern sensibilities and DEI standards) of salvation through Christ alone, This “exclusiveness” Machen explains, “ran directly counter to the prevailing syncretism of the Hellenistic age,” and so too today. He expounds further on the topic saying, “modern liberalism, placing Jesus alongside other benefactors of mankind, is perfectly inoffensive in the modern world. All men speak well of it. It is entirely inoffensive. But it is also entirely futile. The offence of the Cross is done away, but so is the glory and the power.” Then as now, it was exactly the exclusive nature of Christ as the singular savior of man (John 14:6) that so perturbs and enrages our modern society obsessed with the deification of man and erasure of God.

It is also in this chapter that Machen delves deeper into philosophical and social differences and shifts away from his familiar theological arguments. He states how “older evangelism [i.e. his own] was individual; the newer evangelism is social.” And, it is this difference with the emphasis placed on societal change rather than a change within the heart and mind of the individual that Machen so abhors. This systematized liberal doctrine, with Henry E. Fosdick as the contemporary counterbalance to Machen, believed societal causes to be the singular aim of the church undergirded by a less literal and supernatural understanding of Scripture. The salvation and sanctification process are clear and distinct. If everyone was a good person, not in need of a savior or salvation, then the focus logically shifts away from the individual who needs saving and to the society which can be made better through communal efforts put forth by an authority.

Machen then points to a direct repercussion of what was occurring in front of his and has continue to play out to this day. He rightly saw influence being stripped from parents and familial bonds and shifted to the state apparatus. Modern trends were diminishing parental control, with the state influencing school choices and the community taking charge of recreation and social activities (indeed a precursor to our modern predicament). This shift contributed to the breakdown of the home, as children’s lives became more influenced by the utilitarianism of the state than the Christian atmosphere in the home. It was and is only with the “revival of the Christian religion would unquestionably bring a reversal of the process; the family, as over against all other social institutions, would come to its rights again.”

The major point throughout Machen’s work was to show the futility of a Christianity without Christ, a faith without belief, and a God without divinity. He emphasized that applied Christianity is the result of an initial act of God, distinguishing this belief from the modern liberal perspective that sees applied Christianity as the entirety of the faith. Machen’s work and words act as both a guide and a warning. His words are no less true or instructive as they were a century ago. They should also act as a warning to show that if nothing is done, the trends he saw will only get worse.

To end, I should remark I have shared this new tradition with my son, who is now two. While more a passive listener than an active participant during his first year with The Velveteen Rabbi (1922)t, he was much more enraptured with 1923’s pick A Visit from Saint Nicholas or more commonly referred to as Twas the Night Before Christmas. Any recommendations for this year (2024-1924) for myself or my son would be greatly appreciated. Write in with your suggestions. In fact, I would be delighted to choose a book from those suggested and write a follow-up column next year, if the gracious editors would be so inclined.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

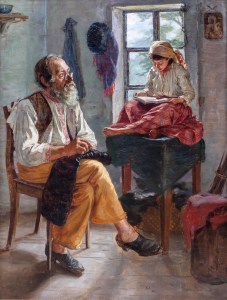

The featured image is “Podczas lektury” (“While Reading) (1886) by Maria Klass-Kazanowska, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.