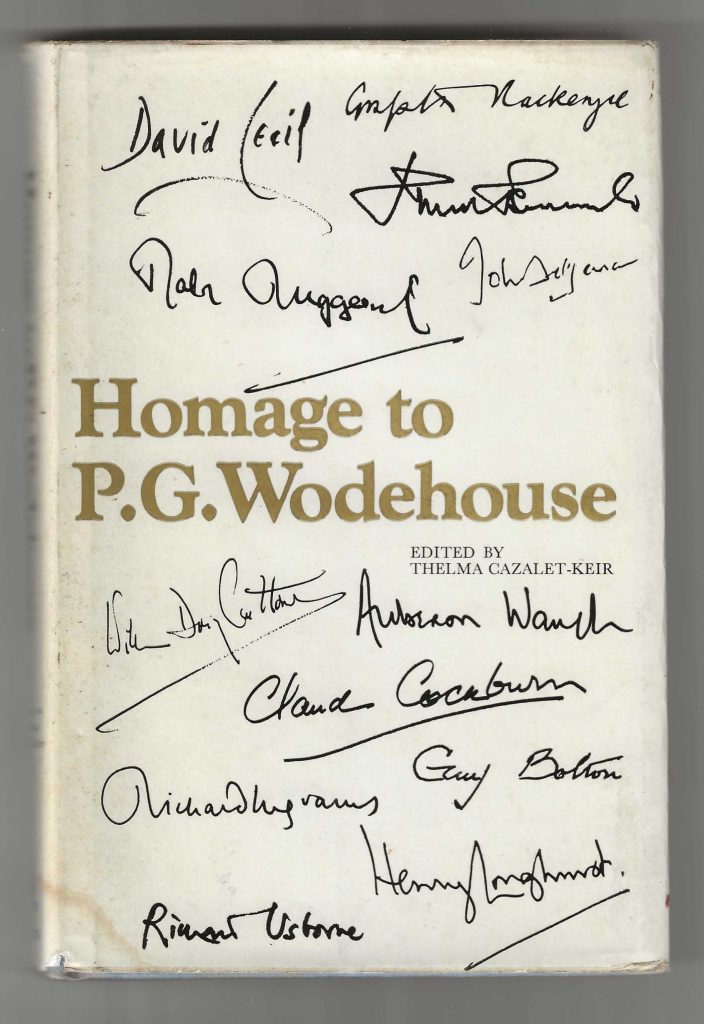

AMONG the treasures in my book collection is a slim volume, Homage to PG Wodehouse. This was compiled in 1973, two years before the Master’s death, by Thelma Cazalet-Keir, a former Tory MP whose brother Peter Cazalet was married to Wodehouse’s beloved stepdaughter Leonora.

Contributors include Malcolm Muggeridge, who was tasked by MI6 with investigating Wodehouse as a suspected traitor during World War II after he made his infamous broadcasts from Berlin. Mugg it was who had to tell Wodehouse in 1944 that Leonora had died under anaesthetic for a minor operation. ‘He stayed silent for a while, and then said: “I thought she was immortal”.’

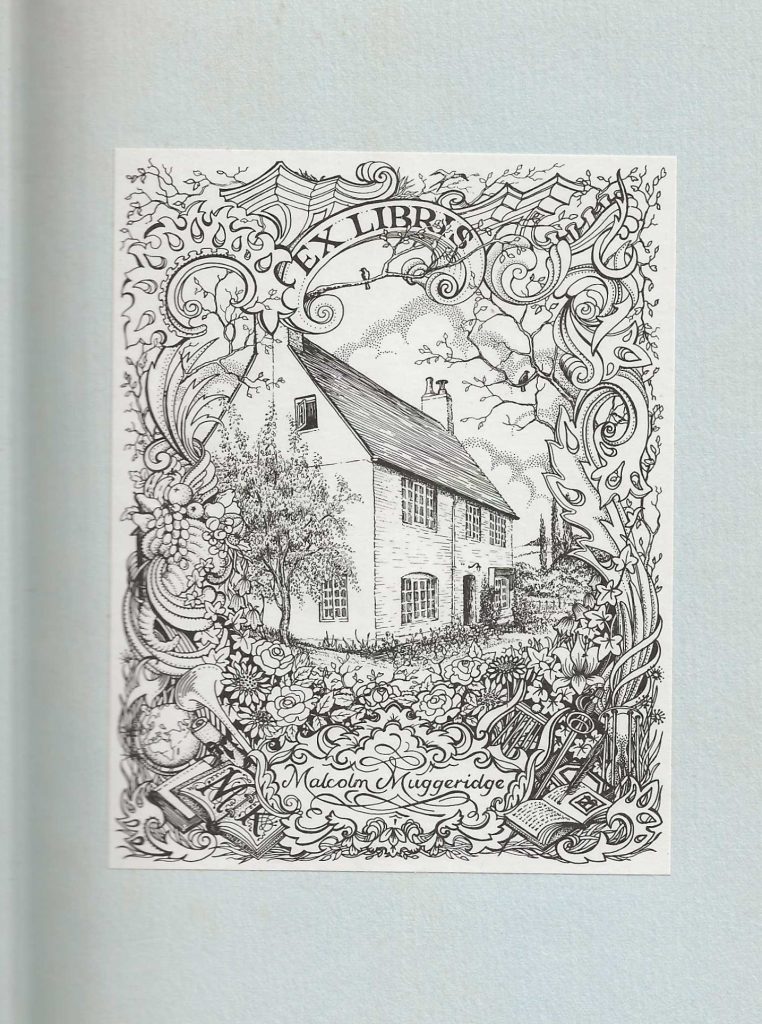

My copy of the book bears the legend ‘Ex Libris Malcolm Muggeridge’. I bought it about 30 years ago, presumably after his family had a clear-out following his death in 1990. I wouldn’t part with it for the world.

The preface is the work of Lord David Cecil (1902-1986), a biographer, historian and scholar. He wrote: ‘Not only am I proud to write of Mr Wodehouse but I feel that I ought to. For it is the function of a professor of English Literature to praise good work and Mr Wodehouse’s work is triumphantly good. The scope and nature of his success indicate his triumph. He appeals to all ages. Evelyn Waugh has written of him, “Three full generations have delighted in Mr Wodehouse. As a young man he lightened the cares of office of Mr Asquith. I see my children convulsed with laughter over the same books.”

‘I too have seen my children convulsed by them and the shelves stocked with his works to be found in any bookshop in the kingdom show that such convulsions are a common phenomenon of present-day England.

‘For me it is in his use of language that Mr Wodehouse’s genius appears supremely. It shines equally in narrative, in description, in dialogue. I have been told that it comes easily to him, and certainly the effect is effortless, but this does not mean that it is careless; on the contrary, again and again he presents one with a concentration of verbal felicities. And – here I must speak as a professor of literature – it is a highly literary style, rich in similes and metaphors and literary allusions and dead idioms brought to vivid life by some unexpected turn of phrase; as when Bertie, urged by Jeeves not to reveal a secret, says, “Wild horses shall not drag it from me; not that I suppose they’ll try!” Or comments, “It is a very rummy feeling when you feel yourself braced for the fray and suddenly discover that the fray hasn’t turned up.”

‘Even quoted out of their context, these phrases make us smile. But every element of Mr Wodehouse’s books – plots, characters, descriptions – makes us smile. It is extraordinary how consistently he maintains a comic tone, a comic perspective. His world owes its enchanting atmosphere of sunshine and gaiety to the fact that not for a moment does it include anything that could possibly have a solemn or painful implication. There are no black jokes in it, no excursions into harsh satire: nor is its clear bright atmosphere blurred with the thinnest shred of sentimental mist.

‘We embark on his books assured that we shall find nothing to make us shudder or reflect or shed tears; but only to laugh. And with a laughter of pure happiness; Evelyn Waugh has said the last word on this aspect of Mr Wodehouse’s art. Let him say it again here: “For Mr Wodehouse there has been no fall of Man: no ‘aboriginal calamity’. His characters have never tasted the forbidden fruit. They are still in Eden. The gardens of Blandings Castle are that original garden from which we are all exiled. The chef Anatole prepares the ambrosia for the immortals of high Olympus. Mr Wodehouse’s idyllic world can never stale”.’

There follows an open letter to Plum from his assiduous biographer Richard Usborne.

‘Dear Mr Wodehouse,’ it begins. ‘Two years ago I came to see you in America. We had been corresponding since about 1957 but I had never met you. My visit to you on Long Island was arranged by letter before I left England.

‘I suggested to The Times in London that, if you approved of it being an interview, I should write it for them. They gave me a green light. So did you. And a very pleasant four or five hours I had at your house and in your garden: and a very good lunch.

‘In my piece for The Times I wrote that I’d asked you how you generated nifties (Monty Bodkin’s word). I instanced “He clutched at a passing table” as a good way of describing a man, much surprised or frightened, steadying himself. “What part of your brain do you use for creating such verbal felicities?” I asked. You didn’t give me any very revealing answer. You said, modestly but not, I think, evasively, that you wrote and rewrote and rewrote, and the thing began to improve.’

Usborne opines that we shall never be told about Wodehouse’s creative processes ‘beyond what you yourself have written . . . that, in settling down to your desk, you have sharpened more pencils and cleaned out more pipes, probably, than any other author. And somewhere else you have written, “I sit down at my typewriter and curse a bit”.’

I hope you have enjoyed these extracts from Homage to PG Wodehouse. Other contributors include Claud Cockburn, Richard Ingrams, Henry Longhurst and Auberon Waugh, and I shall share their words in future columns.

Old jokes’ home

Recently I’ve been attending meetings of Eavesdroppers Anonymous – not that they know!

A PS from PG

It was a harsh, rasping voice, in its timbre not unlike a sawmill.

PG Wodehouse: Laughing Gas