C.S. Lewis thought that “Romanticism” had acquired so many different meanings that, as a word, it had become meaningless “and should be banished from our vocabulary.” But is Lewis right?

In the “Afterword” to the third edition of The Pilgrim’s Regress C.S. Lewis complained that “Romanticism” had acquired so many different meanings that, as a word, it had become meaningless. “I would not now use this word… to describe anything,” he wrote, “for I now believe it to be a word of such varying senses that it has become useless and should be banished from our vocabulary.” He then proceeded to offer no fewer than seven different definitions of Romanticism to prove his point.

In the “Afterword” to the third edition of The Pilgrim’s Regress C.S. Lewis complained that “Romanticism” had acquired so many different meanings that, as a word, it had become meaningless. “I would not now use this word… to describe anything,” he wrote, “for I now believe it to be a word of such varying senses that it has become useless and should be banished from our vocabulary.” He then proceeded to offer no fewer than seven different definitions of Romanticism to prove his point.

Begging to differ with Lewis, we might argue that banishing words is akin to burning books. It should be avoided in the name of freedom of expression and clarity of thought. It is the purpose of the adjective, that noble creature and servant of the truth, to provide the necessary distinguo when the meaning of the noun is unclear. Adding the adjective philosophical to romanticism allows us to understand an important movement in the history of ideas.

According to the Collins Dictionary of Philosophy, romanticism is “a style of thinking and looking at the world that dominated nineteenth century Europe”. Arising in early mediaeval culture it referred originally to tales in the Romance language about courtly love and other sentimental topics, as distinct from works in classical Latin. From the beginning, therefore, “romanticism” stood in contra-distinction to “classicism”. The former referred to an outlook marked by refined and responsive feelings and thus could be said to be inward-looking, subjective, “sensitive” and given to noble dreams; the latter is marked by empiricism, governed by physical science and precise measures, and could be said to be outward-looking.

Understood in this context, philosophical romanticism, which was a major influence on the shaping of nineteenth century culture, could be seen as a reaction against the philosophical materialism of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment.

Although further adjectives are needed to distinguish the romanticism of different countries, each of which reflect national sensibilities, the essential reactionary quality of romanticism with respect to its rejection of the empiricism and scientism of the Enlightenment is common to English, German, French, Spanish and Italian Romanticism. This reaction against the philosophical materialism of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries manifested itself in a renewed interest in the “healthier” centuries which preceded the Enlightenment, resulting in the rise of neo-medievalism, a fascination with the Middle Ages.

In the case of English Romanticism, neo-medievalism emerged in the work of the first generation of Romantic poets. Samuel Taylor Coleridge exhibited a desire for the pre-modern past in the deliberate archaism of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner; William Blake evoked ancient legends in his idealization of England’s “green and pleasant land” and in his anathematizing of the “dark satanic mills” of the Industrial Revolution; Sir Walter Scott championed chivalry in his narrative poetry and in novels, such as Ivanhoe, which is set in twelfth century England; and John Keats, in “La Belle Dame Sans Merci”, captivated readers in his tale of an elven maid’s enrapturing and capturing of a lovelorn knight’s heart and soul.

As romanticism took root in the English psyche, so did neo-medievalism, especially in the form of the Gothic Revival, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Oxford Movement.

The Gothic Revival resurrected the architectural innovations of the thirteenth century, the perpendicular splendour of the high Middle Ages, in contradistinction to neo-classicism’s evocation of pre-Christian Greek and Roman antiquity. The leading light of the Gothic Revival, Augustus Pugin, designed many of the new Catholic churches built following Catholic Emancipation in 1829. He was also the principal architect responsible for the new Houses of Parliament in London, built in the mid-nineteenth century.

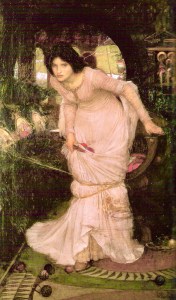

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a movement in the visual arts which sought to revive the aesthetic vison of medieval and early Renaissance art that had existed prior to the artistic innovations of Raphael. The pre-Raphaelites chose themes inspired by Arthurian legends and by Shakespeare’s plays, thereby leapfrogging over the whole period of the Enlightenment to what was perceived as the purer vision of the past.

The Oxford Movement within the Church of England sought to reconnect the Anglican Church with the medieval English Church. Through the adoption of Catholic liturgical forms and an ecclesiology which argued that the Anglican Church was part of the historical Catholic Church, the Oxford Movement developed into what would become known as Anglo-Catholicism. Many of the leaders of the Oxford Movement, including John Henry Newman, would convert to Roman Catholicism. Newman’s conversion in 1845 would signal the birth of the Catholic cultural revival, a movement in the English-speaking world which would place the Catholic aesthetic at the centre and even at the summit of nineteenth and twentieth century culture. Over the next century or so, many of the greatest writers would form a part of this revival: Gerard Manley Hopkins, Oscar Wilde, Francis Thompson, G. K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Robert Hugh Benson, T. S. Eliot, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien, to name an illustrious few.

In closing, it should be acknowledged that romanticism also has its darker side. The dark egocentric subjectivism of the second generation of Romantic Poets, particularly Byron and Shelley, would metamorphose into nihilistic negation and the deconstructionist reductio ad absurdum of postmodernism. Nonetheless, as a healthy reaction to the supercilious presumption of the Enlightenment and its philosophical materialism, romanticism played a major role in reclaiming culture from the cold clutches of scientism and helped to restore the heritage of Christendom to its rightful place at the core of cultural life.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “The Lady of Shallot Looking at Lancelot” (1894) by John William Waterhouse, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.