Whether 1968 really was “the year that broke politics” is, at best, debatable. But it certainly was a year during which past patterns of politics were seriously upended. In other words, the title of Luke A. Nichter’s book is more eye-catching than accurate. Nonetheless, there was collusion and chaos aplenty in that fateful year.

The Year That Broke Politics: Collusion and Chaos in the Presidential Election of 1968, Luke A. Nichter (370 pages, Yale University Press, 2024).

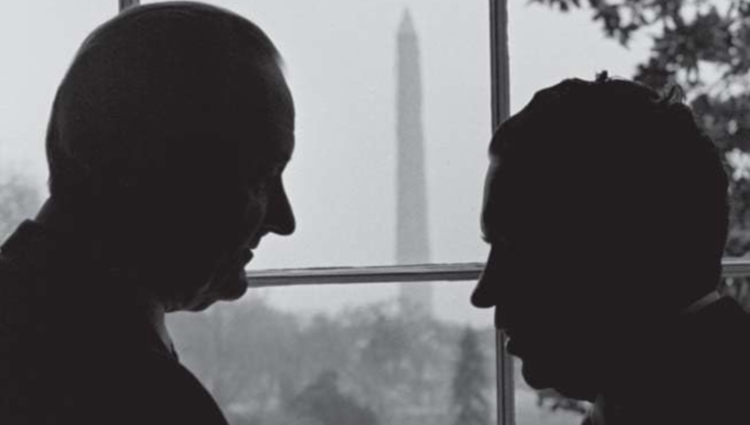

Hiding in plain sight on the cover of this book are two shadowy figures. It turns out that the same pair were just plain hiding from public view, at least on occasion, during the chaotic presidential election year of 1968. Or at the very least they made certain that such was the case whenever they were colluding. Of course, the two are, left to right, the sitting president and his successor, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. Their silhouetted profiles remain unmistakable.

Hiding in plain sight on the cover of this book are two shadowy figures. It turns out that the same pair were just plain hiding from public view, at least on occasion, during the chaotic presidential election year of 1968. Or at the very least they made certain that such was the case whenever they were colluding. Of course, the two are, left to right, the sitting president and his successor, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. Their silhouetted profiles remain unmistakable.

Has Luke Nichter made a mistake by linking them so closely together? Not at all. Did they think that they were erring by cooperating? Or should that be colluding, whether they were doing so together or separately or both? No again. After all, each man got just what he wanted out of their temporary partnership. In Lyndon Johnson’s case he sought to preserve a chunk of his presidential legacy, while Richard Nixon had his eye on finally winning that office.

Actually, if Nichter is correct, and it would seem to be a serious historical mistake to think otherwise, Johnson came away from that election with a double victory. How so? Well, at the risk of being repetitive, he thought he had rescued his legacy and… Richard Nixon wound up in the White House.

Whether 1968 really was “the year that broke politics” is, at best, debatable. But it certainly was a year during which past patterns of politics were seriously upended, if not actually broken. In other words, the title is more eye-catching than accurate. Nonetheless, there was collusion and chaos aplenty in that fateful year.

Nichter opens his book with brief biographies of four of the six major political figures of 1968. Two of the four are Johnson and Nixon. The other two are the eventual Democratic nominee, Vice-President Hubert Humphrey, and a third party candidate, namely former Alabama Governor George Wallace. The two who are missing are Senators Robert Kennedy of New York and Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota.

To be sure, both Kennedy and McCarthy do figure prominently in this story, McCarthy because he had mounted a campaign to challenge Johnson for the nomination and Kennedy because he ultimately, if belatedly, mounted a challenge of his own. But neither senator remained a major factor through the fall campaign, Kennedy because of an assassin’s bullet and McCarthy because, well, because he was Gene McCarthy.

The Minnesota senator liked to say that he was “twice as liberal” as Hubert Humphrey and “twice as Catholic” as Robert Kennedy, but he wasn’t nearly as driven or as ambitious as either of the two. For that matter, he may also have been more than twice as lazy–or surely twice as easily distracted–as either of his rivals of 1968.

Conventional wisdom has it that Robert Kennedy might well have been the eventual Democratic nominee had it not been for that assassin’s bullet. Nichter seems to share this view, but he upends much of the rest of anything else that passes for conventional wisdom about the politics of 1968.

But not everything else. Lyndon Johnson really did despise Robert Kennedy–and vice versa. In fact, had Kennedy been the convention-endorsed nominee of the Democrats in 1968 Johnson likely would have doubled, and perhaps even tripled, his efforts to secure a victory for his long-standing Republican rival, Richard Nixon, come that November. That would be the Richard Nixon whom Johnson had once derisively dubbed as little more or little other than a “chronic campaigner.”

Otherwise, Nichter is bent on challenging conventional wisdom about 1968 at virtually every turn. In that sense, his account is less the story of the year that broke politics than it is his telling a story, or should that be belatedly breaking a story?–that shatters a good deal of the conventional understanding of the politicking of that election year.

If there is a sympathetic political figure to be found in these pages it would have to be the eventual loser of the presidential election, namely Hubert Humphrey. The sitting vice-president was trying to accomplish something that had not been accomplished since Martin Van Buren succeeded Andrew Jackson in 1836 and would not again be accomplished until George H. W. Bush succeeded Ronald Reagan in 1988. That would also be the same task that would not be nailed down in 2024, which has already proved to be another year about which it will likely be said that it, too, “broke” conventional politics amid “collusion and chaos” all its own.

Yes, advancing from the vice-presidency to the presidency in one fell swoop has never been a routine progression in American politics, But it proved to be an especially difficult step for Humphrey to take in 1968, since his ostensible boss, the sitting president, was doing his unlevel best to stand in his way, rather than simply stand aside.

Writing as a long time Minnesotan, it’s more than tempting to add that what proved to be Humphrey’s fate and dilemma couldn’t have happened to a nicer guy. Heck, it might not have happened to Hubert Humphrey, if he had been something other than a nice guy, or at least someone who was, well, someone more like Lyndon Johnson, who was known by many to be many things, none of which happened to fall into the category of “nice guy.”

Nichter deploys Billy Graham on more than a few occasions to help nudge Lyndon Johnson at least a bit closer to that category, if not actually into the Humphrey camp, if only because Graham had deployed himself, at least in part, for that very purpose. For that matter, Graham sought to play a similar role in the life of “comeback kid” Richard Nixon, especially between his back-to-back defeats (for the presidency in 1960 and for governor of California in 1962).

Dubbed the “messenger” by Nichter, Graham also served as an occasional go-between for Johnson and Nixon, as they collaborated to achieve their shared goal of denying the presidency to Vice-President Humphrey.

The two major back stories to their collaboration/collusion were the Paris peace negotiations concerning the war in Vietnam and the Wallace third party candidacy. As Nichter puts it, the “biggest loose end and the least secure part of Johnson’s legacy” was that war. The loose end about it got even looser when McCarthy came close to winning the New Hampshire primary in early March, which prompted RFK to enter the race a few days later.

On March 31, LBJ responded to that political double whammy by delivering a national address in which he called for a bombing halt and peace negotiations before announcing that he would not be a candidate for re-election in November. But Johnson’s withdrawal of his candidacy did not mean that he was withdrawing from politics. Much of the heart of the book then deals with Johnson’s determined and double-pronged effort to achieve a peace that was something other than a unilateral American withdrawal and to make sure that his successor was on that same page.

In a sense this was an early version of legacy achievement courtesy of what President Nixon’s national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, subsequently termed the “decent interval,” meaning the distance between an American military withdrawal from Vietnam and the collapse of the South Vietnamese government. Of course, while he was still the president, Johnson was hoping to achieve an honorable American exit without any sort of a South Vietnamese defeat, much less a collapse.

The loose cannon in all of this was Hubert H. Humphrey. And the willing partner was, guess who, Richard Nixon. Johnson simply couldn’t be certain that Humphrey wouldn’t give away the store; hence the collusion between Johnson and Nixon.

For his part, Humphrey was reluctant to break with Johnson over the war. More than that, he thought he owed the president his loyalty. Nice guys can be that way. But In the end Nichter contends that Johnson and Humphrey actually “betrayed” each other. The first to do so was LBJ who thought he could be more certain of Nixon’s loyalty to his Vietnam war policy than Humphrey’s. Johnson may well have been right about that, given what Nichter regards as HHH’s belated “betrayal” of Johnson by way of his late-in-the-campaign offer of a unilateral bombing halt in order to “woo McCarthy and Kennedy votes.”

In retrospect, perhaps Humphrey’s only hope of snatching victory from defeat would have been to break from Johnson sooner. Sometimes in presidential politics the ticket to success can be running as much against your own party, or at least your own party’s recent history, as opposed to running only against the opposing party. Witness the successes of Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump.

In any case, it is Nichter’s contention that Humphrey’s ultimate decision to go after voters on the left, coupled with Wallace’s pursuit of them on the right, conceded the “broad center” to Richard Nixon, who united the GOP and then managed a slender victory over a “divided Democratic party–with Johnson’s help.” One might even add “considerable help.”

After all, if Luke Nichter is not mistaken, President Johnson’s role in all of this proved to be much more important than any of the usual suspects, whether they be Nixon’s alleged “southern strategy” or his dealing with the South Vietnamese government through intermediaries such as Anna Chennault, the widow of General Clare Chennault.

In the fall campaign Richard Nixon, or the former vice-president who had failed to win the presidency in 1960 as Vice-President Humphrey would fail in 1968, essentially conceded the south to Wallace and ultimately colluded much more effectively with a sitting president than with anyone else.

If there is a lingering footnote to all of this, it might be that Nichter sees the Wallace campaign as based on much more than race. In fact, he contends that it was largely a working class campaign that presaged another such campaign of much more recent vintage. More specifically than that, Nichter discreetly suggests that it signaled the somewhat later rise to power of a successful businessman and successful presidential candidate whose most recently defeated opponent can be now added to the short list of names of defeated-for-president sitting vice-presidents, an abbreviated list that includes that of Hubert Humphrey. Need one be any more specific than that?

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.