FEAR over measles has resurfaced with a push for 900,000 unvaccinated young adults to take the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) jab. This new psyop is cruel. Truth is, measles has been no serious threat since WW1, and by the beginning of WW2 it was considered a mild illness. By then infectious diseases had almost been eradicated without the help of vaccines and by the time the single measles vaccine was introduced in the UK in 1968, measles deaths had already reduced by 99.8 per cent.

In 1941, Life magazine reported: ‘We have reduced death from principal communicable diseases of childhood – measles, scarlet fever, whooping cough, diphtheria – to a new record low, a point actually promising complete eradication of these diseases!’

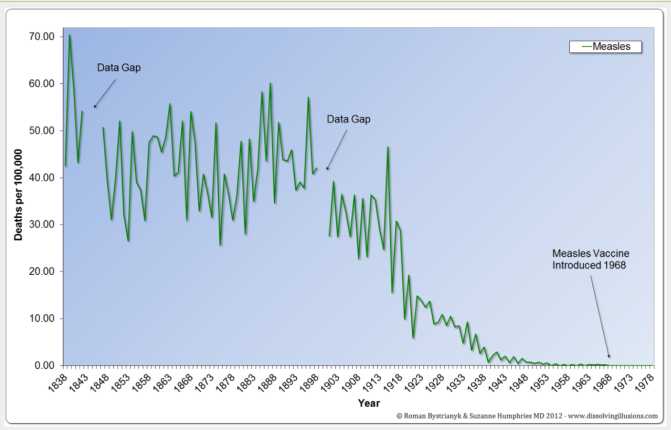

Governments tell us that vaccination is solely responsible for the reduction in infectious disease deaths, but this is clearly not the case as the graph below shows.

Source: Roman Bystrianyk and Suzanne Humphries MD, dissolvingillusions.com

It was the same story in the US: deaths had reduced by 98.6 per cent before the single measles vaccine was introduced there in 1963. (See graph below.)

These graphs are in stark contrast to scaremongering government graphs that cherry-pick the numbers, usually back to around 1950, not 1900, and make it look as though the vaccine did a marvellous job in eradicating measles. The graph below is from the NHS’s Green Book, an online vaccination resource for health professionals. It is focused on cases, and not deaths, and clearly does not show the full story.

So, what really caused deaths from measles to decline? It is simple: better food, better sanitation and better housing. Data wizard and software architect Roman Bystrianyk MSc has some incredible research, which can be found in his book Dissolving Illusions: Diseases, Vaccines, and the Forgotten History, co-authored with Suzanne Humphries MD. Their book has sold 100,000 copies and was recently updated.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, conditions for poor families were appalling and they had little chance to thrive. Children as young as three worked in sordid conditions in factories, rarely seeing daylight, ‘to a point of extreme exhaustion, without open-air exercise . . . but grew up, if they survived at all, weak, bloodless, miserable, and in many cases deformed cripples, and victims of almost every disease’. (Source: Willoughby and Graffenried, Child Labor, 1890)

Overcrowding was rife, offering no chance to quarantine the sick. ‘A health officer found six children, between two and 17, suffering from smallpox in a one-roomed dwelling shared with their parents, an elder brother, and an uncle. They slept together on rags on the floor, with no bed. Millions of similar cases could be cited with conditions getting even worse as diseased victims and their corpses remained rotting among families in single-room accommodations for days, as the family scraped together pennies to bury them.’ (Source: Dorothy Porter, Health, Civilization, and the State: A History of Public Health from Ancient to Modern Times, 1999)

Food was scarce and of poor quality. ‘In France, beggars are numerous, and people die of hunger. In Canada, during the winter, many are starved to death. In Buenos Ayres, numbers live off offals (waste). In upper Peru, the natives eat animals that die of disease. The Chinese do the same . . . In Norway and Sweden, people mix their bread with sawdust.’ (Source: ‘Scanty Sustenance’, The American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge, 1836).

Healthcare could be fatal with bloodletting and an alarming list of remedies: ‘From a standard medical work, Collectanea Medica, London, 1725, we find the following: For Quinsy: powder of burnt owl, burnt swallows, cat’s brains, dried and powdered blood of white puppy dogs. For Colic: wolf’s guts, dried and powdered, old man’s urine, sheep’s excrements’. (Source: Alexander Milton Ross MD, Fallacies and Delusions of the Medical Profession, 1888)

Over decades, overcrowded slums were torn down, sewage removed from the streets, hygiene introduced with handwashing, industry moved away from cities, air pollution caused by sulphurous coal burning improved, unions and child labour laws introduced, milk improved – in Chicago, ‘milk came from cows fed on whiskey slops with their bodies covered with sores . . . New York’s milk supply was largely a by-product of the local distilleries, and the milk dealers were charged with the serious offence of murdering annually eight thousand children.’ (Source: Arthur Charles Cole, The Irrepressible Conflict 1850-1865: A History of American Life Volume VII, 1934)

Antibiotics were not widely available until the mid-to-late 1940s. The smallpox vaccine, developed in 1796, divided the medical profession with many speaking against it. In the late 1800s, Louis Pasteur was experimenting with typhoid, cholera and rabies vaccines. Around 1900, an early version of the BCG inoculation was developed to protect against TB, but there was no mass vaccination to speak of until 1942 (the year after Time had heralded the death of infectious disease) with the introduction of the diphtheria vaccine. No vaccine was ever developed for the bacterial illness scarlet fever, yet the numbers declined in lockstep with other infectious disease.

This history is irrelevant to our health agencies who have ramped up the fear. In February the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) run by Dr Jenny Harries issued national guidelines designed to terrify parents into vaccinating their children and pregnant women into taking the jab. ‘Measles is highly infectious, the most infectious of all diseases transmitted through the respiratory route. Measles can be severe, particularly in immunosuppressed individuals and young infants. It is also more severe in pregnancy, and increases the risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, or preterm delivery.’ UKHSA said 900,000 young adults were unvaccinated, nearly a million, which raises the question, ‘why do we only have 733 cases if measles is so infectious?’

Dire predictions of a public health disaster from the BBC, who reported that computer modelling showed that a huge measles outbreak was expected to affect up to 160,000 people in London alone, failed to materialise. In England and Wales, there has been an increase from 209 cases in January to 733 in March in a population of 66million. Dr Liz Evans, founder of the UK Medical Freedom Alliance (UKMFA), describes measles as ‘an uncomplicated and self-liming disease for the vast majority of those who catch it’. Read Dr Evans in more detail here.

Times have changed and infectious diseases are no longer life-threatening to healthy people. The rationale to vaccinate is that measles, which textbooks used to call ‘mild’, is now classified as ‘nasty’. The illness typically lasts for around ten days with the worst symptoms on days three to six. A rash appears on the body, accompanied by cold symptoms, conjunctivitis, a dry cough and a mild to moderate fever.

Secondary symptoms such as bacterial pneumonia (treatable with antibiotics) and ear infections cause concern, but these are rare. Extremely rare complications include encephalitis (inflammation of the brain tissues) and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE), a degenerative neurological disease that usually manifests years after recovery.

However, the vaccine can also cause these side-effects. Government say this is limited to one in a million and that measles causes problems in one in 5,000. What they do not clarify is that the one in a million figure comes from the number of successful vaccine injury claims – which are notoriously difficult to prove. Doctors rarely make the association, having been taught at medical school that vaccines are safe, and parents often do not connect the dots. Those who do are likely to find themselves gaslit.

A high-profile MMR injury case was Robert Fletcher, now in his early 30s, who suffered severe brain damage after his first MMR at 13 months and needs 24/7 care. The Mail on Sunday reported on its front page that his family fought for 18 years before the government recognised his vaccine injury. In 2010, the Fletchers were finally paid pathetic compensation of £90,000.

The UKHSA were asked to respond to the anomaly between their limited figures and the big picture. They sent over some ‘background’ information which admits the risk of catching measles is ‘very low’. The rest of the ‘background’ is demonstrably untrue as the above graphs show.

They said: ‘The risk of catching measles in this country remains very low as the number of the number of people unvaccinated in the UK is a very small proportion of the overall population. We are not currently considered an endemic measles country thanks to the MMR immunisation programme, and reduced travel during the pandemic. However, this situation can change rapidly, and it is essential that people make sure they have their MMR vaccine to ensure the risk of catching measles does not increase.’