In one of his last writings, Pope Benedict XVI afforded a key insight into the conservative ideal. Though he was writing as a Catholic about Catholic problems, the late pope’s reflections are truly universal.

In one of his last writings, Pope Benedict XVI afforded a key insight into the conservative ideal. Though he was writing as a Catholic about Catholic problems, the late pope’s reflections are truly universal.

Speaking directly to the sexual abuse crisis that reached fever pitch during his pontificate, Benedict observes: “The crisis caused by the many cases of clerical abuse drives us to regard the Church as a failure, which we must now decisively take into our own hands and redesign from the ground up.”

This, he warns, is dangerous. If the Church can be “redesigned from the ground up,” it cannot be what the Scripture says it is—the gift of God. If the Church can be manhandled, it must also be man-made—just another work of human hands, with nothing unique or precious to offer the world.

In this sense, Benedict says that “a Church that we build can offer no hope.” Indeed, for Benedict, “the idea of a better Church of our own creation is really a proposal of the devil.”

While Benedict’s reflections take for granted traditional Christian dogma on the nature of the Church, his reflections are equally salient in regard to secular politics. If we are conservatives of the traditional, Russell Kirk school, we see the society into which we have been born like how Benedict sees the Church: It is a gift, given to us to be cherished, not fundamentally changed.

Respect for what Kirk calls “prescriptive society”—a society whose fundamental structures are “givens”—invokes the same humble attitude toward the world that Benedict has toward the Church. Change, in this view of things, must be organic and patient. It is not a process of “evolution,” where a mutation fundamentally changes the species, but of “development,” where what is already present comes more fully to fruition.

We are most tempted to disregard this point of view in moments of crisis. The French Revolution was not a reasoned, organic process, but a boiling-over of generations of anger. The society it produced looked nothing like what it replaced. It wore many of the same clothes, but was altogether different.

Because of the Revolution, we must admit that some things got better. But many others did not. The Revolution’s modest gains in the area of human dignity hardly justify the amount of human blood it spilled, in France and across Europe.

Benedict and Kirk would likely agree that the idea of a better America of our own creation is really a proposal of the devil. This would be true whether the “better” America was of liberal or conservative design. The temptation to manhandle society is akin to the temptation to manhandle the Church: It denies the fundamental givenness of the world as we have received it.

For one who views life from the perspective of Scripture, there is nothing uniquely modern about the temptation to manhandle the world. It is the pattern we see throughout the story of the Bible: Crisis forces people, again and again, to choose between submitting to truth—with all its attendant helplessness—and exercising raw power, taking matters into our own hands.

Exposing and repenting of this tendency forms, in a certain sense, the core of conservative thinking, whether secular or religious. Either society is a given, something precious that forms us and provides the context of our life, or it means nothing.

Benedict’s reflections on reform in a time of crisis apply equally to life inside and outside the Church. The priority of truth over raw power lies at the heart of all genuine renewal.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

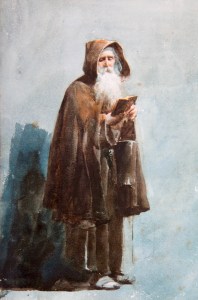

The featured image is by Josep Tapiró, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.