SINCE Storms Babet and Ciaran at the end of October, which ushered in an unusually wet winter, as noted by the Hydrological Summary (HS) (1), the incidence of groundwater flooding has made the headlines in several parts of the UK. As usual the mainstream media have treated the floods in their usual shock-horror fashion, rather than treat it for what it is, a not very common but perfectly normal pattern to the way that groundwater behaves.

Groundwater occurs widely across England and Wales and provides the major regional aquifers (bodies of rock and/or sediment that hold groundwater) such as chalk, limestone, greensand and sandstone, forming some of the prominent landscape features including the South Downs, the Cotswolds and the North Yorkshire Moors. See map below.

Aquifers in England. Green-Chalk; Dark Blue-Jurassic Limestone; Yellow-Sandstone; Light Blue-Carboniferoue Limestone; Purple-Magnesian Limestone. Source; UK Hydrologicl Summary, February 2024.

Each of these areas has its particular landscape features, prominent among which are dry valleys, ephemeral (seasonal) streams, potholes and subterranean cavern systems. Most importantly, especially in southern England, the aquifers have provided a perennial water source. Major public water supply facilities have been developed since the late 19th century, but prior to that village water supplies from wells had been used for centuries. Many municipal supplies were constructed on spring-sites, as in Brighton, Sutton (Surrey) and at various locations in East Anglia. Such is the nature of chalk and other limestone aquifers that the abstraction of large volumes of water can be made in a carefully managed fashion without permanent damage to the aquifer and superficial environmental deterioration. The experts in the study of behaviour, resource development and monitoring are hydrogeologists.

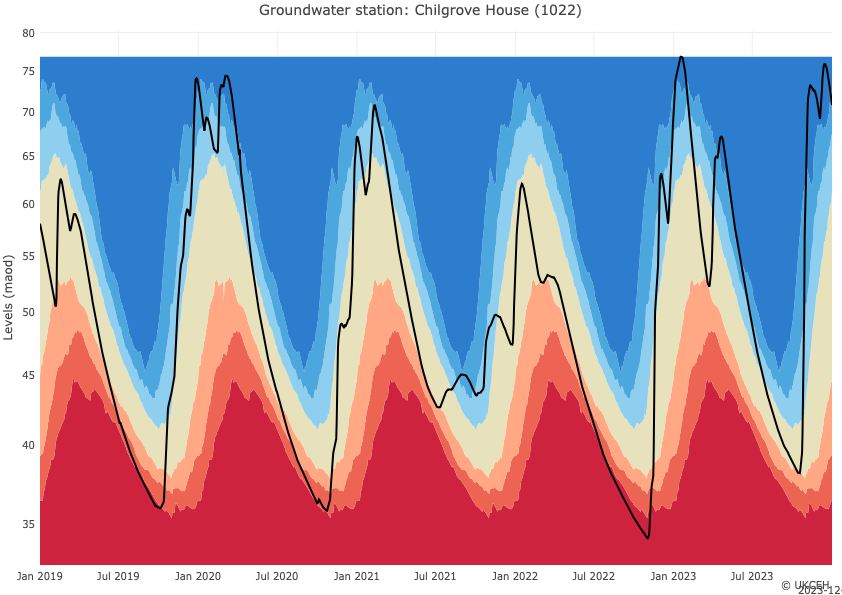

Hydrogeological cycles and extremes occur in all aquifers, and the seasonal fluctuations are a very good indicator of water resources conditions. This diagram for the Chilgrove House observation well near Chichester is a good illustration of the way groundwater levels fluctuate annually.

Groundwater Hydrograph, 2019-2023, Chilgrove House, Sussex. Source: UK Water Resources Portal, UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology.

The diagram also illustrates the range over which water levels can change – up to 35m (115ft) in a year. The rises in groundwater are periodically evident at the surface by flow appearing in headwater streams and increasing the flow in the lower downstream portions. Water levels at Chilgrove are directly linked to flow in the River Lavant, and high flows often cause flood problems in and around Chichester, where there has been considerable expansion of the city, and at times these floods have caused significant problems with culverted sections and on the Chichester by-pass, constructed in the 1990s.

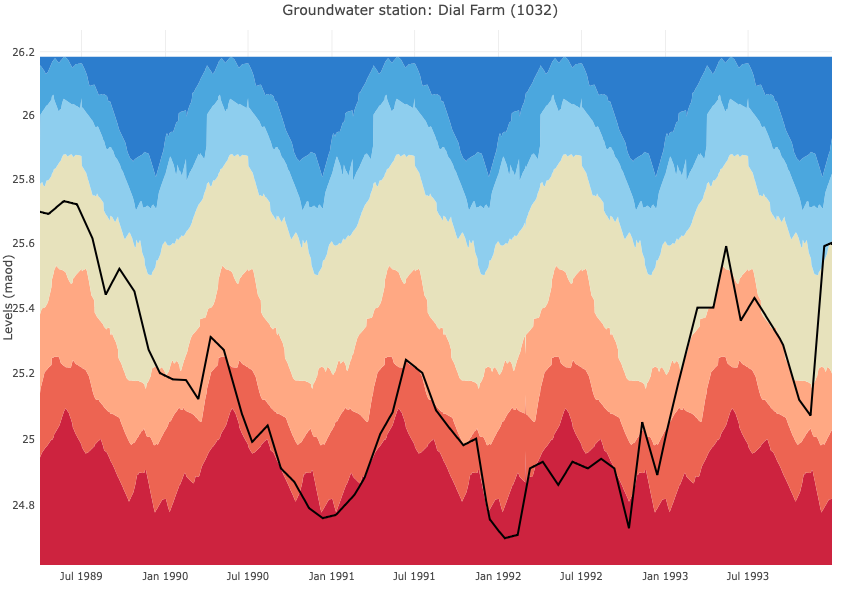

The widespread development of groundwater as a major resource has not been without problems, especially due to over-abstraction and prolonged droughts, when rainfall fails to replenish the aquifer during the winter. Better understanding of the groundwater cycle has changed many concepts of groundwater development. In the 1960s and 70s, major groundwater schemes were undertaken in the Thames and Lower Great Ouse catchments, primarily for low-flow support to rivers and for security of public water supply to major urban areas, such as Reading, London and Essex. Major networks of long-distance pipelines were constructed, fed by deep boreholes abstracting from the aquifer. It was thought, perhaps naively, that the top of the aquifer could be ‘skimmed off’ with minimal effect to the environment, but significant drought in the mid-70s and early 90s showed this idea to be erroneous, with water features such as the Thames headwaters and Breckland Meres drying up. Some parts of these major schemes have indeed been mothballed, and river support pumping instigated for environmental and aesthetic reasons. The diagram below shows the depressed water levels at Dial Farm, near Ipswich, throughout the drought from 1990-94, when water restrictions had to be applied.

Observed groundwater level (maod) at Dial Farm observation borehole,1989-94. Source: UK Water Resources Portal, UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology.

I was fortunate enough to work as a consultant to English Nature, and was tasked with reviewing drought management plans for some water companies and Wildlife Trusts with wetland sites, and it was clear that environmental issues were taken seriously. Outside water supply, on which society is dependent for drinking and agriculture, groundwater risks are ever-present for building foundations. With the decreasing use of industrial water and the cessation of pumping with mine closure, rising groundwater is a perennial problem in many areas. But there is no need to panic. Like most other natural phenomena, groundwater is well understood, and unusual events need not be treated as portents of doom. Not unless of course, one is a MSM operator, politician or celebrity, intent on climbing on the Net Zero bandwagon.

Reference:

The Hydrological Summary for the UK is published at the end of each month by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (CEH). It contains data from the national monitoring networks for rainfall (Environment Agency and Met Office), river discharge (EA), groundwater level (British Geological Survey) and soil wetness (CEH).