Set in Yorkshire, England on Christmas Eve, Russell Kirk’s short story “Saviourgate” is a story about the soul’s journey through the afterlife. Whereas many ghost stories explore only the diabolical imagination, “Saviourgate” opens up creative possibilities for thinking about life’s timeless moments and how they may be glimpses of paradise.

Ghost stories were standard Christmas Eve fare in Victorian England as the darkest night of the year is more proximate to Christmas Eve than Halloween. Charles Dickens’ renowned A Christmas Carol showcased Scrooge’s transformation after visits from the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future. North American writers continued this tradition well beyond its Victorian roots. In Canada, Robertson Davies read a newly penned ghost story each Christmas season from 1961 until 1983 as Master of the University of Toronto’s Massey College. Elsewhere, American horror writer Stephen King located his supernatural nativity tale, “The Breathing Method,” during a Manhattan Christmas in homage to this Victorian tradition.

Ghost stories were standard Christmas Eve fare in Victorian England as the darkest night of the year is more proximate to Christmas Eve than Halloween. Charles Dickens’ renowned A Christmas Carol showcased Scrooge’s transformation after visits from the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future. North American writers continued this tradition well beyond its Victorian roots. In Canada, Robertson Davies read a newly penned ghost story each Christmas season from 1961 until 1983 as Master of the University of Toronto’s Massey College. Elsewhere, American horror writer Stephen King located his supernatural nativity tale, “The Breathing Method,” during a Manhattan Christmas in homage to this Victorian tradition.

Though best known for his political theory and social commentary, Russell Kirk wrote more than twenty ghost stories as “experiments in the moral imagination” to explore both the noble side of humanity as well as the loathsome. Eerdmans’s published a near-complete collection of these tales in 2004’s Ancestral Shadows, where readers will find more than one-third of the stories set in Kirk’s native Michigan. However, Kirk situated several of his tales in the British Isles, with one being a clear tribute to the traditional Victorian ghost story.

Set in Yorkshire, England on Christmas Eve, Kirk’s short story “Saviourgate” bears an epigraph from the 14th- century Yorkshire funeral song “Lyke-Wake Dirge,” signaling that this will be a story about the soul’s journey through the afterlife. This dirge outlines a harrowing, purgatorial trek across a thorny moor, the Bridge of Dread, and a purgatorial fire. In the tale, Kirk surprises the reader by carrying not only the soul but also the body into a paradisical afterlife with memories, expectations, and longings intact. The fire in “Saviourgate” is a cozy charcoal fire in a British hotel parlor, in contrast to the more jolting purgatorial fires of the “Lyke-Wake Dirge.” Before going further, it’s important to better understand how Russell Kirk viewed the afterlife and how one’s views of the soul’s journey through the afterlife impacts one’s moral imagination.

The Myth of the Otherworld Journey

A helpful guide to Kirk’s thinking on the afterlife is his September 1992 lecture at Hillsdale College “The Myth of the Otherworld Journey” Shortly after Kirk’s death in April 1994, this lecture was published in the now defunct magazine The World & I in October 1994 as “The Salutary Myth of the Otherworld Journey.” This lecture and subsequent essay explore the positive social impact of centuries and centuries of myth-making of the soul’s journey through the afterlife noting, “For three thousand years and more, the myth of the otherworld journey has done much to restrain the pride and the passions of men and women” (p. 437). He notes how these myths continue to evolve from ancient times to the 20th century and how, when properly presented, these myths provoke one’s moral imagination.

Kirk acknowledges milestones in British and American writings that explore the otherworld journey, including Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress and Lewis’ The Great Divorce. He notes his own 1979 contribution, the novel Lord of the Hollow Dark, but most readers will find “Saviourgate” both more accessible and more readily available. Admittedly, several of his ghostly tales reference the otherworld journey, including “Watchers at the Strait Gate” and his award-winning “There’s a Long, Long Trail A-Winding.” “Saviourgate” is unique among his tales in that the pilgrim journeys into the otherworld and then back out. With the above lecture and essay in the background, one can more easily understand Kirk’s goal of adding his own salutary myth for modernity with a clear focus on Paradise rather than Purgatory.

A Cozy Hotel on Saviourgate

By Kirk’s own admission, “Saviourgate” draws inspiration from Dante’s Divine Comedy, but the protagonist’s path bears more similarity to T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets than to Dante’s medieval journey. The tale begins with travelling businessman Mark Findlay lost and wandering, not in a dark wood, but in a 1970’s Eliot-style wasteland. Late at night, the deathly ill Findlay turns into a picturesque street populated with welcoming homes and a luminous Norman church at the far end tolling its bell. As he staggers and coughs, he is pulled into the well-managed Crosskeys Hotel which he finds vaguely familiar from a prior visit on Christmas Eve 1939 when he was a soldier. A friend from the war, Ralph Bain, welcomes him to The Crosskeys and helps him settle into a comfortable, well-appointed parlor. Whereas Dante’s purgatorial transformation was more of a trial by fire, Kirk offers Mark Findlay the chance at transformation at fireside in a hotel parlor with good company, good food and drink, and lively conversation.

Though Kirk was Catholic, this is a more Protestant story populated with an Anglican canon modeled after Kirk’s own friend, Canon Basil A. Smith. In the Divine Comedy, Dante is alive and his guide, Virgil, is a shade (or ghost). In “Saviourgate”, Kirk flips the script with the protagonist, Mark Findlay, portrayed as a ghost and his guides are not just alive but, as one notes, “fully alive.” Kirk uses the conversation among Findlay, Bain, and Canon Hoodman to examine various notions about the passage from life to death and what comes after— all the while the “good sound” of the bell tolls outside. In the end, Findlay declines the invitation to stay at The Crosskeys, choosing instead to return to his life as a husband and businessman. Like Scrooge, he transforms and returns, but Kirk suggests that he could have also transformed and continued his otherworldly journey.

Bain walks Findlay outside to bid farewell. Findlay turns to thank him for a strange but invigorating evening only to discover The Crosskeys Hotel gone, the bell silent, and the scene replaced by a bombed-out street. Biographer Brad Birzer notes that Kirk had a similar experience during a trip to England, where he suddenly saw a street that had not been there in decades only to have it just as suddenly disappear. Kirk may have grown his own “timeless moment” into this short story. Findlay asks his cab driver the name of the now derelict street, and the driver responds, “Saviourgate, sir.”

Eliot’s Timeless Moments

In his “Salutary Myth” essay Kirk noted that, “the myth of the otherworld journey continues to grow” (p. 436). He also pointed out that “one poet of the otherworld journey builds upon the perceptions of his poetic predecessor” (p. 427). Kirk built his own salutary myth of the otherworld journey primarily upon T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. Eliot’s poems suggest that brief, timeless moments of piercing beauty are widespread across humanity: “The moment in the arbour where the rain beat, The moment in the draughty church at smokefall.” Kirk lengthened one of his own timeless moments into a short story about the possibilities of life after death—or, as Anglican theologian N.T. Wright puts it, “Life after life after death.” Whereas many ghost stories explore only the diabolical imagination, Kirk’s “Saviourgate” opens up creative possibilities for thinking about life’s timeless moments and how they may be glimpses of paradise.

A Personal Reflection

I have sensed several of Eliot’s timeless moments in my own life. Let me offer one in contrast to Mark Findlay’s more extroverted, community-centered moment. I remember a Western-themed den with a gas-heated, faux-rock fireplace in the back corner of my grandparent’s home in Snyder, Texas. Whenever my father and mother travelled to Snyder for a family visit, I more and more dwelled in this room. Alone and comfortable in my introversion, the muffled voices of my parents and grandparents broadcast from other rooms in the house giving me a great sense of security. It was here that I first read parts of Treasure Island by the light of the wagon-wheel chandelier. Later, I would discover this was my father’s personal volume on the den’s bookshelf. It was here that my young imagination soared as I watched the unbelievably exhilarating (at the time) King Kong vs. Godzilla on the old black-and-white tabletop television set. Though alone, this introvert found a generative space where his moral imagination began to grow. Kirk’s salutary myth of the otherworld journey helps me think differently about Jesus’ words, “Today, you will be with me in Paradise” (Luke 23:43). Maybe I will enter that room alone. Maybe He will join me. Maybe we will sit and read together. And maybe we will keep going.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

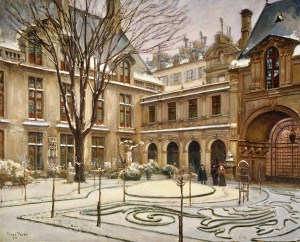

The featured image is “Le jardin du musée Carnavalet , effet de neige” (1905) by Charles Henry Tenré, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.