Do journalists have a constitutional right to keep sources confidential? That question sits at the heart of a dispute over a Fox News report from Catherine Herridge seven years ago. Herridge, who recently got unceremoniously and strangely terminated by CBS News in the Paramount Minus downsizing, used a confidential source within federal law enforcement to publish information from an investigation into a Chinese-American scientist that eventually went nowhere.

Yanping Chen wants to recover damages and punitive awards from the officials who leaked the investigation to Herridge. Herridge refuses to name her source(s) despite a court order to do so. Late yesterday, the federal judge overseeing the case held Herridge in contempt and began fining her $800 a day, although he stayed the ruling to allow Herridge to appeal:

Herridge sat for a deposition in late September but refused to reveal how she obtained the information, citing her First Amendment rights and telling Chen’s lawyer, “I must now disobey the order.”

“The Court does not reach this result lightly,” the judge wrote. “It recognizes the paramount importance of a free press in our society and the critical role that confidential sources play in the work of investigative journalists like Herridge. Yet the Court also has its own role to play in upholding the law and safeguarding judicial authority.”

Herridge’s attorney, Patrick Philbin, said he and his client “disagree” with the judge’s decision and intend to appeal it.

“Holding a journalist in contempt for protecting a confidential source has a deeply chilling effect on journalism,” Fox News said in a statement. “Fox News Media remains committed to protecting the rights of a free press and freedom of speech and believes this decision should be appealed.”

Judge Christopher R. Cooper did give Herridge time to appeal, so the fines do not begin immediately. Cooper rejected Herridge’s offer to pay a nominal $1 daily fine, which Cooper said would not provide any incentive for “ensuring compliance” with this and similar orders. However, Cooper also rejected a plaintiff motion that requested Cooper order that Herridge not be allowed to have third parties pay the fines for her, which means Herridge can get some help if this drags out. Herridge also isn’t sitting in a jail cell, at least not yet, which other reporters have had to do in this circumstance. (If she refuses to pay the fine, that could change, of course.)

Herridge already has built-in sympathy. She’s a hard-nosed reporter with plenty of connections. She also reports fairly, without bias, and like her former CBS colleague Jan Crawford, has built trust among both conservatives and liberals. (I am a big fan of both.) The Chen report came amid a series of hacks by China against US governmental systems and an ongoing massive theft of intellectual property by the CCP through any means possible. There’s no doubt about the valid public interest in sussing out China’s activities in the US and those who might be facilitating them or worse.

But given that the probe apparently turned up no actionable violations, Chen seems to have a valid complaint to pursue. Her access to potential target systems, plus questions about Chen’s background, had prompted the federal probe, but those investigations are supposed to remain confidential because people are presumed innocent until enough evidence accumulates for a public indictment. Instead, someone leaked the probe to Herridge and transmitted confidential documents including photographs and “images of internal government documents,” the Post notes. Fox News published that material, which Chen argues violated her privacy and damaged her reputation. Someone connected to the investigation broke the rules in giving this to Herridge, although those rules don’t apply to Herridge or reporters. Chen wants to impose consequences on the leakers, but has to go through Herridge to get to them.

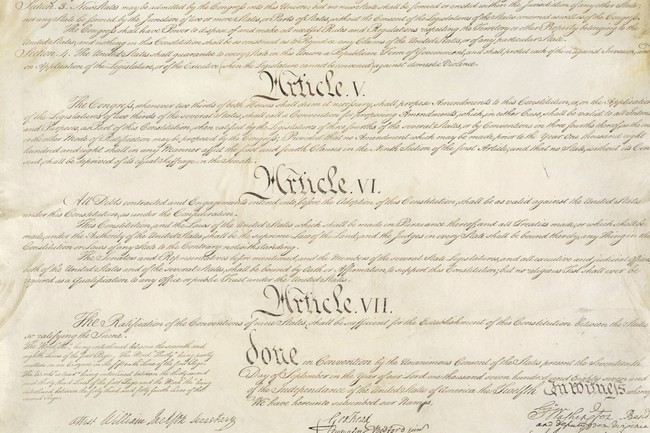

All of this brings us to this question: do reporters have a First Amendment right to keep their sources confidential? And the answer to this is … no, they do not. Federal courts have customarily avoided the kind of confrontation we see in this case, and states have passed laws granting statutory privilege to refuse to reveal sources. But we occasionally see federal cases come down to this conflict, and reporters have sat in jails for months on end for their refusals.

That doesn’t mean a confidential-source privilege would be a bad policy, although Congress has refused to grant it as a statutory privilege, likely for reasons I’ll cover later. Regardless, it doesn’t exist as a First Amendment right. Cornell Law has a brief but meaty explainer on the First Amendment and the protection of confidential sources:

The Court observed that Congress, as well as state legislatures and state courts, are free to adopt privileges for reporters. As for federal courts, Federal Rule of Evidence 501 provides that the common law generally governs a claim of privilege. The federal courts have not resolved whether the common law provides a journalists’ privilege.

Nor does the status of an entity as a newspaper (or any other form of news medium) protect it from issuance and execution on probable cause of a search warrant for evidence or other material properly sought in a criminal investigation, the Court held in Zurcher v. Stanford Daily. The press had argued that to permit searches of newsrooms would threaten the ability to gather, analyze, and disseminate news, because searches would be disruptive, confidential sources would be deterred from coming forward with information because of fear of exposure, reporters would decline to put in writing their information, and internal editorial deliberations would be exposed. The Court thought that First Amendment interests were involved, but it seemed to doubt that the consequences alleged would occur. It observed that the built-in protections of the warrant clause would adequately protect those interests and noted that magistrates could guard against abuses when warrants were sought to search newsrooms by requiring particularizations of the type, scope, and intrusiveness that would be permitted in the searches.

Essentially, this comes down to a balancing of interests, which is a function of the judiciary in disputes. If Chen didn’t have a substantial case or the information needed was trivial to it, Cooper would have refused to order Herridge to respond. Clearly, Cooper thinks that Chen has enough of a case for serious consideration and that Herridge’s information is more important to the cause of justice in this case than the damage that would be done in revealing the source who violated the rules. That is a tough call in any instance, and may be even more so in this one given Herridge’s reputation as a responsible and reliable journalist.

Consider this from another angle, one that may be a lot less hypothetical these days. Imagine a federal prosecutor — who wields enormous power — decides that he despises a particular public or non-public figure, but can’t get enough evidence for an indictment. He then decides to leak investigatory documents to a reporter in order to ruin the person’s reputation and hopefully force him to cooperate — or to convince others to come out of the woodwork to provide the evidence that would close the gap for an indictment. And now imagine that the target of this leak campaign turned out to be innocent in the first place. The confidential source in such a scenario wouldn’t be a whistleblower, but a manipulator who politicized the process of justice for his own personal ends.

Such a scenario was the basis of the excellent 1981 film Absence of Malice, starring Sally Field, Paul Newman, and Wilford Brimley. We’ve seen enough prosecutorial misconduct over the last few years to make that hypothetical a real possibility. And if it happened to you, would you not want justice from the court over that abuse of power?

That could be what happened with Chen, although we can’t know that until we know who leaked the material and why. That wouldn’t be Herridge’s fault — she was doing her job — but that doesn’t make the potential injustice and damage any less for Chen. The role of the court is to weigh all of the interests and rule in the interests of justice.

I agree that there is a very serious public interest in keeping sources confidential, which should weigh heavily in the balance in cases such as these. I also believe that there is a very serious public interest in not allowing people in federal law enforcement to manipulate the media and the public with selective leaks from confidential investigations. Given the widespread abuse of anonymous sourcing by the mainstream media these days, I’d be more inclined to let the judiciary balance these interests than grant the media and those in power a blanket immunity from accountability, as imperfect a process as that may be — and even when a damned fine reporter like Herridge gets caught up in the conflict.