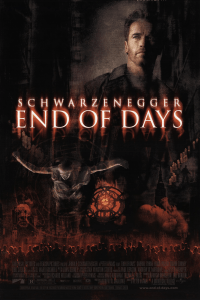

There is a world of difference between the dark arts and the art of darkness. Truth be told, there is more than a world of difference; there is a hell of a difference and a hell of a distance. It is the difference and the distance between heaven and hell. The dark arts are evil whereas the art of darkness is the depiction of evil. Evil art makes sin attractive, denying its sinfulness and seducing us with the lie that it is only a pleasure to be grasped when the opportunity presents itself. Such art reduces all morality to mere ambivalence and ambiguity, replacing the truths of religion with the mere opinions of the relativist. The art of darkness, on the other hand, shows the ugliness of sin and illustrates its destructive consequences. It is not evil art but the realistic portrayal of evil in art. It is not sinful but is full of sin. This crucial distinction came to mind as I was watching End of Days, a “chilling supernatural action thriller” starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Ironically and absurdly, considering the darkness of its theme, it could be classified as a “holiday movie” because it is set in the Christmas season, leading up to the climactic scene on New Year’s Eve. It is about as festive, however, as Die Hard, which is also sometimes considered a “holiday movie” because of its Christmas setting.

There is a world of difference between the dark arts and the art of darkness. Truth be told, there is more than a world of difference; there is a hell of a difference and a hell of a distance. It is the difference and the distance between heaven and hell. The dark arts are evil whereas the art of darkness is the depiction of evil. Evil art makes sin attractive, denying its sinfulness and seducing us with the lie that it is only a pleasure to be grasped when the opportunity presents itself. Such art reduces all morality to mere ambivalence and ambiguity, replacing the truths of religion with the mere opinions of the relativist. The art of darkness, on the other hand, shows the ugliness of sin and illustrates its destructive consequences. It is not evil art but the realistic portrayal of evil in art. It is not sinful but is full of sin. This crucial distinction came to mind as I was watching End of Days, a “chilling supernatural action thriller” starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Ironically and absurdly, considering the darkness of its theme, it could be classified as a “holiday movie” because it is set in the Christmas season, leading up to the climactic scene on New Year’s Eve. It is about as festive, however, as Die Hard, which is also sometimes considered a “holiday movie” because of its Christmas setting.

Released in 1999 as the world approached the new millennium, End of Days is about satanism and the efforts of satanists to sacrifice an innocent young woman to the devil. Satan is himself present in the outward form of an investment banker whom he has possessed. His goal is to seduce the woman who had been “baptized” in the blood of a snake by satanists shortly after her birth, marking her as the devil’s “bride”. Their infernal union would lead to the birth of the Anti-Christ and the apocalyptic “end of days”.

The film is full of interesting theological scenarios, much more interesting than the relentlessly dark and evil figure of Satan himself, who is ultimately as sterile as his creed of mere negation. There is the depiction of the pope, clearly St. John Paul II, though he is not named, who orders that the woman be protected as an innocent victim, even though some of his advisers want her killed as the means of thwarting the devil and the prophesied apocalypse. There is a mysterious medieval order of priests, intent on killing the woman, thereby embracing the tempting but illicit employment of evil means to a purported good end.

There is the presence of temptation, which transcends and supersedes the presence of the Tempter, because it presents moral dilemmas, the choice between good and evil, which Satan in his stagnant stasis is incapable of making. Mere mortals can teeter on the brink of the chasm between heaven and hell. Satan has nothing but hell. “I am more than a devil; I am a man,” says Gabriel Syme, the protagonist of Chesterton’s novel, The Man Who was Thursday. “I can do the one thing which Satan himself cannot do – I can die.” Choosing to die to oneself that others might live is the very secret of life as it is the secret of love. This is the choice faced by the protagonist of End of Days. In learning to lay down his life for others, in learning how to love, he learns how to live. When we first see him, he is putting a gun to his own head, on the brink of suicide; when we last see him, he sacrifices his life to save the girl and thwart the devil. He reminds us of Hamlet, who similarly contemplates suicide when we first see him but ends by laying down his life so that the “something rotten” in the state of Denmark can be purged. Horatio prays over Hamlet’s body that flights of angels might sing him to his rest; the protagonist of End of Days ends in a deadly but ultimately life-giving embrace with a statue of Michael the Archangel, Satan’s nemesis.

There is the presence of temptation, which transcends and supersedes the presence of the Tempter, because it presents moral dilemmas, the choice between good and evil, which Satan in his stagnant stasis is incapable of making. Mere mortals can teeter on the brink of the chasm between heaven and hell. Satan has nothing but hell. “I am more than a devil; I am a man,” says Gabriel Syme, the protagonist of Chesterton’s novel, The Man Who was Thursday. “I can do the one thing which Satan himself cannot do – I can die.” Choosing to die to oneself that others might live is the very secret of life as it is the secret of love. This is the choice faced by the protagonist of End of Days. In learning to lay down his life for others, in learning how to love, he learns how to live. When we first see him, he is putting a gun to his own head, on the brink of suicide; when we last see him, he sacrifices his life to save the girl and thwart the devil. He reminds us of Hamlet, who similarly contemplates suicide when we first see him but ends by laying down his life so that the “something rotten” in the state of Denmark can be purged. Horatio prays over Hamlet’s body that flights of angels might sing him to his rest; the protagonist of End of Days ends in a deadly but ultimately life-giving embrace with a statue of Michael the Archangel, Satan’s nemesis.

None of the foregoing should be seen as an endorsement of the film per se. Some of it is silly. Some of it is sordid, especially the sex scene in which the devil perverts sexual desire pornographically into homosexual incest. Such sordidness is, however, part of the art of darkness. It shows sin to be ugly and disgusting. It does not show it to be a harmless pleasure but a destructive vice. Another film, Unfaithful, does something similar in its sordid portrayal of the destruction of a marriage and the ruining of a child’s life caused by adultery. There are parallels in literary fiction. We think perhaps of The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde and especially of the novels of Joris Karl Huysmans. Such films and such works of fiction are not for the pure of spirit. Such souls will be unnecessarily slimed and sullied by uncomfortably close encounters with things they have blissfully never imagined. No, End of Days is not for the young or the innocent, nor are the works of Huysmans, but they serve as powerful cautionary reminders for those tempted by sordidly seductive pleasures that such pleasures have infernally destructive consequences.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Images are courtesy of IMDb.