“Dred Scott” is a landmark decision because it answered questions regarding slavery that the Supreme Court had not previously addressed. It is also one of the most infamous decisions, furthering the great divide facing the nation regarding the question of slavery and moving the country further down the path toward the Civil War.

Dred Scott was born into slavery in Virginia around 1799, but was moved to Missouri where he was sold to Dr. John Emerson, an army surgeon. Given Dr. Emerson’s military career, he moved frequently and took Scott with him. Eventually, Dr. Emerson moved with Scott to the State of Illinois and the Territory of Wisconsin, both free territories. While in the Wisconsin Territory, Scott married Harriett Robinson, another slave who was also sold to Dr. Emerson. In 1838, Dr. Emerson married Eliza Irene Sandford from St. Louis. In 1843, Dr. Emerson died shortly after returning to his family from the Seminole War in Florida. His slaves continued to work for Mrs. Emerson and were, as was common at the time, occasionally hired out to others. In 1846, Dred and Harriet Scott each filed suit in St. Louis to obtain their freedom, on the basis that they had lived in a free state and territory, and the rule in Missouri and some other jurisdictions at the time was “once free, always free.” When the suit reached the Supreme Court of the United States, the main issue presented was whether slaves had standing to sue in federal courts.

Dred Scott was born into slavery in Virginia around 1799, but was moved to Missouri where he was sold to Dr. John Emerson, an army surgeon. Given Dr. Emerson’s military career, he moved frequently and took Scott with him. Eventually, Dr. Emerson moved with Scott to the State of Illinois and the Territory of Wisconsin, both free territories. While in the Wisconsin Territory, Scott married Harriett Robinson, another slave who was also sold to Dr. Emerson. In 1838, Dr. Emerson married Eliza Irene Sandford from St. Louis. In 1843, Dr. Emerson died shortly after returning to his family from the Seminole War in Florida. His slaves continued to work for Mrs. Emerson and were, as was common at the time, occasionally hired out to others. In 1846, Dred and Harriet Scott each filed suit in St. Louis to obtain their freedom, on the basis that they had lived in a free state and territory, and the rule in Missouri and some other jurisdictions at the time was “once free, always free.” When the suit reached the Supreme Court of the United States, the main issue presented was whether slaves had standing to sue in federal courts.

Background of the Case

Numerous precedents in Missouri case law, including Rachael v. Walker (1837) established the legal principle of “once free, always free.” The judge declared a mistrial when the case was heard in 1847, and when it was retried in 1850, the St. Louis court ordered Dred Scott free—the Scotts agreed that only Dred’s case would proceed in order to save money and avoid duplicate efforts and all parties agreed that the outcome of Dred’s case would also apply to Harriet. In Scott v. Emerson (1852), the Missouri Supreme Court decided against Scott, reversing the lower court decision, and noting that Missouri law would not be subject to outside anti-slavery arguments. By its decision, the Missouri Supreme Court overturned the long-held principle of “once free, always free.” The Missouri Supreme Court explained its decision in stark terms and why it was overruling precedents:

Times are not now as they were when the former decisions on this subject were made. Since then not only individuals but States have been possessed with a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable consequences must be the overthrow and destruction of our government.

The Controversy

Seeking to have the Supreme Court of the United States opine on the legality of Missouri’s invalidation of the “once free, always free” principle, Scott’s attorneys filed a new suit in federal court, Dred Scott v. John F.A. Sandford (Sanford’s name was misspelled due to a clerical error).

The United States District Court for the District of Missouri directed the jury to consider the question of whether Scott was free or a slave based on Missouri law. Based on the Emerson decision, the jury found that Scott was a slave.

The Supreme Court Decision

Scott appealed to the Supreme Court. Initially, the Supreme Court was inclined to affirm the Missouri Supreme Court decision based on Strader v. Graham (1851), a decision of the Supreme Court allowing the Court to affirm a state supreme court decision without hearing it on the merits. However, some of the justices suggested that the Supreme Court address issues that until then remained unresolved, including those that Sanford’s attorneys raised during the federal lawsuit, such as Scott’s ability to sue in federal court and whether a black person could be a citizen of the United States. The main issue before the Supreme Court was whether Scott had ever been free.

Delivered on March 6, 1857, the Court, by a 7-2 decision, held that blacks were not and could not be citizens of the United States and, as a result, Scott lacked standing to sue in federal courts. The Court also found that Scott had never been free, finding that Congress exceeded its authority when it forbade or abolished slavery in the territories, invalidating the Missouri Compromise. Having found a lack of standing, this second issue should not have been addressed by the Court. Chief Justice Roger Taney wrote for the majority:

In discussing this question, we must not confound the rights of citizenship which a State may confer within its own limits and the rights of citizenship as a member of the Union. It does not by any means follow, because he has all the rights and privileges of a citizen of a State, that he must be a citizen of the United States. He may have all of the rights and privileges of the citizen of a State and yet not be entitled to the rights and privileges of a citizen in any other State. For, previous to the adoption of the Constitution of the United States, every State had the undoubted right to confer on whomsoever it pleased the character of citizen, and to endow him with all its rights. But this character, of course, was confined to the boundaries of the State, and gave him no rights or privileges in other States beyond those secured to him by the laws of nations and the comity of States.

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 405 (1857).

Conclusion

The Dred Scott decision is a landmark decision because it answered questions regarding slavery that the Court had not previously addressed. It is also one of the most infamous decisions, furthering the great divide facing the nation regarding the question of slavery and moving the country further down the path toward the Civil War. The Dred Scott decision undermined the prestige of the Supreme Court and legal scholars consider it to be the worst decision ever issued by the Supreme Court. The Dred Scott decision was overturned when the Civil War ended and the Civil War Amendments were ratified.

Republished with gracious permission from Constituting America.

This essay was first published here in March 2020.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Bibliography:

Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) Supreme Court decision, 7-2

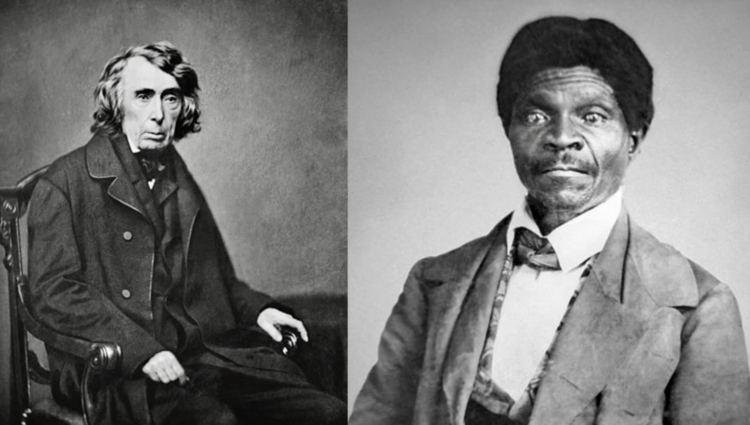

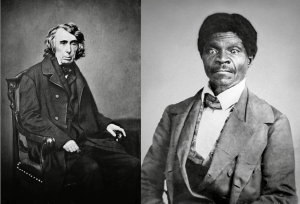

The featured image depicts Dred Scott (right) and Roger B. Taney (left), the latter of whom was the author of the majority opinion in the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision. Both images are in the public domain, and both are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.