PITTSBURGH, Pennsylvania — A couple of weeks ago, a repairman named James came to my home to run a gauge on my stove to check if it was emitting carbon dioxide, as feared by the gas range company. After polite conversation, the repairman and I started to discuss politics, as one does when you are a reporter curious about how a varied swath of the population feels about politics, and James, who was born in Connellsville and lives in Jeannette, said he was unhappy with both front-runners, former President Donald Trump and President Joe Biden.

He said he would “maybe” reluctantly vote for Trump if the election were between the two men and then asked why voters have to settle for either: “Why can’t a third-party candidate ever get off the ground?”

A fair question, given that his dissatisfaction was very reflective of what has been showing up in national polling as it becomes more and more likely it will indeed be Trump and Biden come November.

In December, an Associated Press/NORC poll and an Economist/YouGov survey showed the majority of voters feel anywhere from somewhat to very dissatisfied with their choices if Trump becomes the Republican nominee and Biden remains the Democratic nominee.

Paul Sracic, an adjunct fellow at Hudson Institute and political science professor at Youngstown State University, said the conversation questioning the two-party system that is inching closer to another Trump and Biden matchup is ripe around kitchen tables in this country. Both men have very low favorability ratings.

“The funny thing here is both parties seem determined to nominate the one candidate who could possibly lose to the other,” Sracic said.

Which begs the question, is there any possibility of the United States electing a third-party candidate?

“The answer is yes, but not the way you think,” Sracic said.

Historically, there are several problems that plague third-party candidacies. First, many of these candidates aren’t really in the race to win. Instead, they see entering the race as a way of publicizing a matter or ideology that they find important.

In short, it is fairly unlikely, for example, that Jill Stein, Ralph Nader or Jo Jorgensen, all of them running independently of the two major parties, ever really thought they were going to be sitting behind the desk in the Oval Office.

Sracic said while those kinds of third-party candidates cannot win, what they can do is siphon off votes from candidates who are competitive.

“Voters understand this, and even those who find a third-party message appealing worry that their support will not only be wasted on an unelectable choice but might even result in their least favorite candidate claiming the presidency.”

That’s why a Catch-22 plagues third-party challengers: Candidates must present a credible path to victory before being accepted as serious contenders.

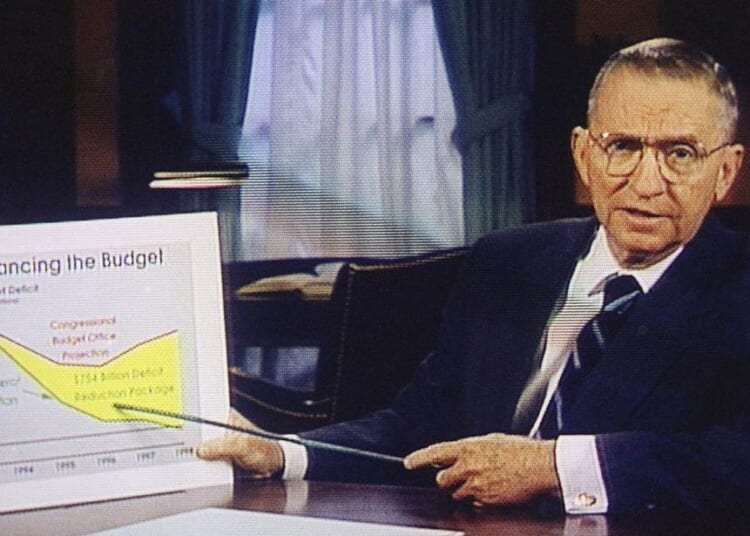

Wealthy businessman Ross Perot was able to manage this early on in the 1992 race between him, then-incumbent Republican president George H.W. Bush and Democrat Bill Clinton, but Perot self-destructed as Election Day drew near.

Sracic said Perot’s campaign was helped by the fact that his populist arguments against budget deficits and trade deals didn’t come off as being radical or outside the mainstream.

“There is a lesson here for 2024: A serious third-party candidate has to be seen as someone who pulls votes from both sides of the aisle, if for no other reason than to offset the fear that they are mere spoilers for one party or the other,” he explained.

People of a certain era still argue whether Perot took more votes from Clinton or Bush in 1992.

Although Perot garnered nearly 20% of the popular vote during his first run, he didn’t make a dent in the vote that really counts: those cast by electors in their states.

Sracic said what if, however, there were a third-party candidate who, like Perot, borrowed from both parties and did not pretend to be able to secure the 270 electoral votes required by the Constitution.

He pointed to the “12th Amendment” strategy George Wallace took in 1968 in his attempt to throw the election into the House of Representatives.

Sracic explained that the approach of Wallace, an undeniably reprehensible racist, was to deny either of the major-party candidates a majority, with the hope he, Wallace, would win a plurality of the popular vote and, therefore, in his mind, force the House to make him president.

“Let’s imagine a slightly different scenario in 2024,” Sracic said. “What if the candidates are Trump, Biden and a third-party centrist, the kind of candidate your repairman was looking for.”

Assuming electoral results similar to 2020, the third-party candidate would only have to win a handful of states to throw the election into the House: Pennsylvania, Virginia and New Jersey would do the trick, Sracic explained.

“Well, the 12th Amendment mandates that the House select from among the three top electoral vote winners and that the vote be taken by state,” he explained.

“A simple majority of state delegations is necessary for election. According to House precedents (from 1825), a tied delegation is considered ‘divided’ and doesn’t count toward the 26 state delegations that a winning candidate must secure,” he said.

Were the House to elect a president, party-line votes are assumed. Under U.S. law, electoral votes are not counted until Jan. 6, a date that, after 2021, we are all familiar with.

Sracic said that date is also important because it is three days after the new Congress is assembled. “Therefore, it is the new Congress, not the old Congress, which would elect the president.”

The Republicans now have a majority in 26 state delegations. But with a change of party in only one seat in any one of eight of those delegations, the state would either be tied or go to the Democrats.

So, a serious third-party candidate would have to concentrate not only on winning a small number of electoral votes but also on fielding congressional candidates in these states or in a state that is deadlocked.

The goal would not be to win in the first round but to deny the major parties a majority. While a centrist third-party candidate would not be the first choice of either party, they would likely be the “least bad” alternative.

The strategy boils down to winning the electoral votes of a handful of states plus fewer than a dozen House seats.

“That was definitely a long answer to the ultimate question of how voters can possibly come together for an independent, bipartisan president that stands a chance of bringing a very fractured nation together,” he admitted, adding, “That approach would be more successful than a third-party candidate trying to get to 270” electoral votes.

Salena Zito is a CNN political analyst, and a staff reporter and columnist for the Washington Examiner. She reaches the Everyman and Everywoman through shoe-leather journalism, traveling from Main Street to the beltway and all places in between. To find out more about Salena and read her past columns, please visit the Creators Syndicate webpage at www.creators.com.